Hammer was a small, family-run British film production company that once dominated the global horror market and remains hugely influential. Hammer resurrected the gothic icons discarded by Hollywood after the war in stylish, sexy and violent films that captured the essence of the original literary form, and functioned as dark reflections of the conventional costume drama in much the same way that gothic narratives inverted nineteenth century realist discourse. Although the golden age of Hammer ended in the early-seventies, the brand remains synonymous with horror, and the studio, much like Dracula, has recently risen from the grave.

Will Hammer was the stage name of William Hinds, who co-founded the film distribution company Exclusive with cinema owner Enrique Carreras in 1934. Hammer Productions Ltd was a symbiotic offshoot. The first Hammer film was The Public Life of Henry the Ninth (1935), a rags-to-riches comedy. Hammer followed this with The Mystery of the Marie Celeste (1936), a tale of insanity, revenge and murder starring Bela Lugosi. Hammer made only three more films before going bankrupt during the British film industry slump of 1937. Exclusive, however, survived.

After the war, Exclusive cut a deal to supply low-budget supporting features to the ABC cinema chain and Hammer was reformed as a production subsidiary in 1947. The first project was River Patrol (1948), a thriller about nylon smugglers. Hammer next adopted the astute formula of adapting established radio serials, for example Dick Barton, Special Agent (1948) and The Adventures of P.C. 49 (1949). Exclusive registered ‘Hammer Film Productions Ltd’ in 1949 with the father-and-son teams of Enrique and James Carreras, and William and Tony Hinds as company directors. Hammer moved into the Exclusive offices in Wardour Street, renaming the building ‘Hammer House.’ In 1951, the company purchased Down Place (one of the best known buildings in gothic cinema), later expanding the house into Bray Studios. Hammer worked like a small studio, building a repertory company of domestic talent at Bray.

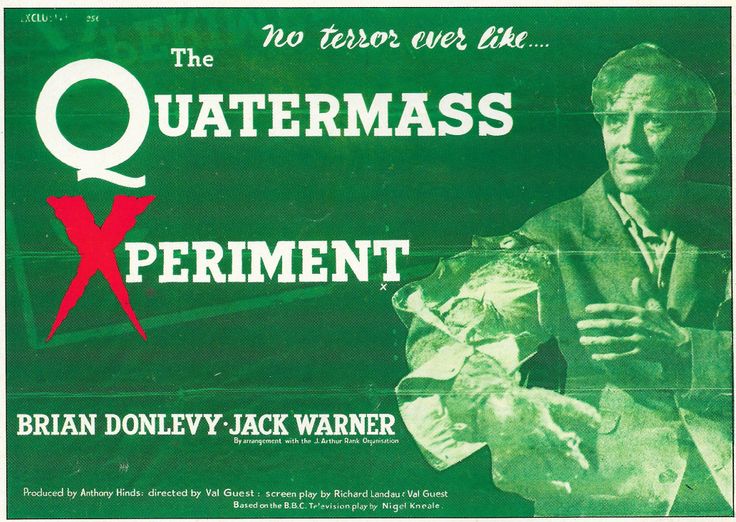

Filming Nigel Kneale’s popular BBC sci-fi-shocker The Quatermass Experiment in 1955 was an obvious next move. The Quatermass Experiment is a very British combination of Edwardian science fiction and Hollywood monster movies. Professor Quatermass puts Britain’s first rocket into space, and it returns with one traumatised survivor infected by an alien force that slowly transforms him into a monster. Richard Wordsworth plays the tragic astronaut with the kind of pathos and dignity that Karloff had brought to Frankenstein (1931). The film grossed almost £1,000,000 worldwide. Maurice Sellar has argued that Hammer moved towards horror in this period because of the competition with television, which did not offer enough sex and violence (Sellar: 1987, 134), while Adkinson, Eyles and Fry cite Hammer’s own market research, that audiences preferred humanoid monsters over outer space blobs (Adkinson et al: 1981, 29). Hammer therefore made the monumental move towards the gothic.

British gothic cinema was not without precedent. Ealing’s anthology horror film Dead of Night (1945) had been a major success, while the United Kingdom was the cradle of the gothic novel. There was also a gap in the international market after the collapse into self-parody of Universal Studios’ monsters, while smaller companies, meanwhile, were targeting a new teenage demographic, and dumbing down accordingly. The world was far from prepared for Hammer’s adult, violent, bleak and morally complex re-invention of The Curse of Frankenstein in 1957. Terence Fisher directed, and the British character actor Peter Cushing was cast as Baron Victor von Frankenstein, with the relatively unknown, but very tall, Christopher Lee playing his creation. Visually, the style was theatrical rather than Expressionist (as had been the case with the Universal Studios classics of the 1930s), and the influence of the Victorian stage and the pre-war revivals of George King and Tod Slaughter were apparent through period melodramadrama. Universal denied Hammer the right to use Jack Pierce’s design for Karloff’s monster, and the critical orthodoxy is that this represents a lack, although it could equally be argued that further distance from the stereotype was an advantage. Whereas Karloff played it with the soul of a troubled child, Lee’s creature is agile, brutal and animalistic while Cushing’s baron is cultured, brilliant, arrogant, and utterly ruthless, murdering Professor Bernstein for his brain, and using his creature to dispose of his pregnant maid, Justine. The creature is finally destroyed with acid, and only Victor’s assistant, Paul Krempe, knows the truth. Victor is charged with Justine’s murder and Krempe lets him go to the guillotine. The film is framed by Victor’s confession from the condemned cell. Although made for a mere £65,000, the film is beautifully shot in Eastmancolor with convincing sets, costumes and effects, and a rich musical score. The acting is impeccable; Cushing’s dignified performance, in particular, gave the film a gravitas rarely seen in the genre before or since. The film still outraged domestic reviewers, with C.A. Lejeune of The Observer describing it as ‘among the half-dozen most repulsive films I have ever encountered’ (McCarty: 1984, 20). Audiences, however, queued around the block and The Curse of Frankenstein was the most successful British film of the year.

Hammer were quick to follow up using the same principal cast and crew, releasing Dracula the next year, with Lee as the Count and Cushing as Van Helsing. Scriptwriter Jimmy Sangster’s Dracula has more in common with Polidori’s Ruthven than Stoker’s savage immortal: Lee’s Byronic vampire was handsome and sexually magnetic, and when he bit, his victim closed her eyes in obvious ecstasy. Cushing’s edgy and driven Van Helsing was the perfect nemesis, and the film’s climax – as Van Helsing hurls himself at ancient drapes, and drives Dracula into the corrosive sunlight with crossed candlesticks – is an iconic moment in cinema. The visual style is perfect, and this gothic mise-en-scène became Hammer’s signature style. Domestic critics hated Dracula even more than Frankenstein, with Lejeune famously apologising on behalf of British Culture to ‘all decent Americans for sending them a work in such sickening bad taste.’ A minor moral panic erupted, and it became trendy for journalists to denounce Hammer as ‘For Sadists Only’ (McCarty: 1984, 20; Hutchinson: 1974, 44). Sadism sold, however, and Dracula was a huge international success. Impressed, Universal executives made their entire back-catalogue available to Hammer.

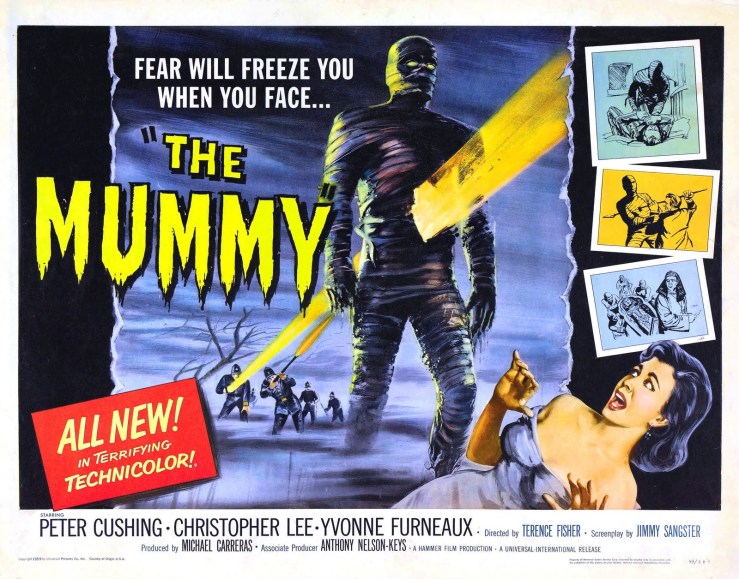

This was the beginning of Hammer’s gothic golden age. Victor returned in The Revenge of Frankenstein (1958), his priest beheaded and buried in his place. The Mummy followed in 1959 (again starring Cushing and Lee and directed by Fisher). Fisher directed The Two Faces of Dr Jekyll, and The Brides of Dracula in 1960; Oliver Reed moved from supporting actor to star in The Curse of the Werewolf in 1961; while Herbert Lom became The Phantom of the Opera in 1962. Traditional gothic themes continued to be reworked in the sixties, alongside a steady stream of second features in other genres, from comedy to war to psychological thrillers. There were three Frankenstein sequels starring Cushing: The Evil of Frankenstein (1964); Frankenstein Created Woman (1967); and Frankenstein Must Be Destroyed (1969); while Lee reprised his role in Dracula: Prince of Darkness (1966); Dracula Has Risen from the Grave (1968); and Taste the Blood of Dracula (1969). The Mummy also returned, twice, and Fisher directed the gothic fairytale The Gorgon in 1964. The Gorgon took a magical realist turn that can also be seen in John Gilling’s The Plague of the Zombies in 1966, which is period and surreal, and looks back to Jacques Tourneur and Val Lewton rather than forward to George A. Romero. The dream sequence where the zombies rise from their graves has been endlessly copied. In characteristic ‘Rep’ style, the Hammer team made fifty-nine films between 1960 and 1969, so Cushing also starred in Captain Clegg (1962), and She (1965), while Lee can be seen in two pirate and four Fu Manchu films, Rasputin: The Mad Monk (1966), and The Devil Rides Out (1968). In 1966, Hammer also worked with Ray Harryhausen on One Million Years BC, starring Raquel Welch and a bunch of stop-motion dinosaurs, while Peter Rogers and Gerald Thomas affectionately sent up the studio and its output in Carry On Screaming. Hammer moved to Elstree Studios in 1967, and received the Queen’s Award for Industry the following year, closing out the decade with Moon Zero Two, a sci-fi western.

The sixties saw competition and change. American International Pictures’ ‘Poe Cycle’ (from The Fall of the House of Usher, 1960, to The Tomb of Ligeia, 1964), starring Vincent Price and directed by Roger Corman, were a direct challenge, while in the UK Tigon had co-produced Michael Reeves’ seminal Witchfinder General with AIP (1968), while Amicus were specialising in EC comics inspired portmanteau horror, often using Hammer talent; Dr Terror’s House of Horrors (1964), for example, starred Cushing and Lee and was directed by Freddie Francis. More worryingly, next to Romero’s eerily postmodern Night of the Living Dead (1968), the traditional gothic of Hammer suddenly looked very dated.

Hammer in the seventies was compelled to respond to market changes, updating settings, which usually didn’t work, and sexing-up, which did. Lee began the decade with Scars of Dracula (1970), but was transported to a contemporary setting for Dracula AD 1972 (1972), and the apocalyptic The Satanic Rites of Dracula (1973), scenarios to which he objected, refusing to play the Count again. The Horror of Frankenstein (1970) stars Ralph Bates instead of Peter Cushing, and is a black comedy. The series ended with Frankenstein and the Monster from Hell in 1974. Cushing’s Baron by then completely mad, the film is set in an asylum. Dr. Jekyll and Sister Hyde (1971) combined elements of Jack the Ripper with Burke and Hare, and the moment when Ralph Bates turns into Martine Beswick is certainly memorable. The Legend of the Seven Golden Vampires (1974) is a curious Kung-Fu collaboration with the Shaw Brothers that might have worked ten years later, while Captain Kronos: Vampire Hunter (1974) was a pilot for a TV show that never was. The last truly gothic Hammer films were the so-called ‘Karnstein Trilogy’: The Vampire Lovers (1970), Lust for a Vampire (1971), and Vampire Circus (1972), all loosely based on J.S. Le Fanu’s Carmilla (1872), with an emphasis on the lesbian possibilities of the story. Both gothic and erotic, these films look great and remain very popular within contemporary ‘goth’ fashion circles. To The Devil a Daughter (1976) had an international cast and high production values, but was too late to catch The Exorcist wave, and The Lady Vanishes (1979) flopped so badly it almost bankrupt the studio.

The studio was also still popular enough in the era of punk rock to support The House of Hammer magazine between 1976 and 1978, an influential publication that combined articles about classic and contemporary horror cinema with graphic adaptations of Hammer films. House of Hammer was the brainchild of the visionary British editor Dez Skinn, and for my generation – pre-video and reliant on our parents for permission to watch the horror double bills on summer Saturday nights on BBC 2 – this was the gateway to horror and the introduction to Hammer, although the only studio release concurrent with the magazine was To The Devil a Daughter.

Down, but not yet out, Hammer produced two TV horror series in the eighties before finally ceasing production: Hammer House of Horror, and Hammer House of Mystery and Suspense. Each series comprised thirteen self-contained horror stories with contemporary settings, Hammer stalwarts and American guest stars. Some were garden variety, others, like the ghost story ‘The House that Bled to Death’ (1980), traumatised a generation.

After effectively going dormant, Hammer’s original gothic style nonetheless remained a mise-en-scènic benchmark, to the extent that when Kenneth Branagh and Francis Ford Coppola both claimed to return to the original nineteenth century gothic texts in their interpretations of Dracula (1992) and Frankenstein (1994), they had ‘Hammer’ scrawled all over them in blue light, blood and black lace, while Jake West’s Razor Blade Smile (1998) was a clear and honest homage, as was Tobe Hooper’s underrated Lifeforce in 1985.

In 2007, Dutch producer John De Mol acquired Hammer via his consortium Cyrte Investments, gaining the rights to over 300 Hammer films and restarting the studio. The Hammer revival began in earnest the following year, with the company producing Matthias Hoene’s Beyond the Rave, a twenty-part serial about modern vampires originally released on MySpace. This was followed by a co-production credit on Let Me In (2010), a remake of the 2008 Swedish film Let the Right One In (Låt den rätte komma in) with the action shifted to New Mexico starring Chloë Grace Moretz as the immortal child, Abby. In 2011, Hammer released the stalker thriller The Resident – which includes a cameo by Christopher Lee and is again set in the US – and Wake Wood, an atmospheric blend of Pet Sematary and The Wicker Man shot and set in Northern Island which could be argued to represent a symbolic and semiotic return to the ‘classic’ Hammer style of edgy, British gothic.

For many fans, the rebrand was cemented in 2012 with the excellent adaptation of Susan Hill’s novel The Woman in Black starring Daniel Radcliffe and directed by James Watkins, a beautifully realised and genuinely frightening Victorian ghost story. This was followed by The Quiet Ones in 2014, directed by John Pogue, a period piece set in the early-seventies about an off-the-grid poltergeist experiment conducted by an Oxford academic. Although not a critical success, The Quiet Ones was an interesting, understated film that managed to evoke the craze for the occult at the time – for example the ‘Enfield Haunting’ – and the TV drama that reflected it such as Nigel Kneale’s The Stone Tapes and the Christmas ghost stories of Lawrence Gordon Clarke, while at the same time exploiting the current enthusiasm for found footage supernatural horror reignited by the success of Paranormal Activity in 2007. In terms of narrative and visual style, it would not have looked out of place as an episode of Hammer House of Horror.

To date, the last Hammer film to be released was The Woman in Black: Angel of Death (2015), directed by Tom Harper, being a sequel to The Woman in Black set in the Second World War, with the notorious Eel Marsh House now a military psychiatric hospital. The film is visually slick, but more ‘Hollywood’ than its predecessor, which detracts from the combination of classic and contemporary gothic that Watkins achieved in the original. Hammer’s latest project, Winchester Mystery House – presumably based on the reputedly haunted mansion in San Jose, California – is under development and scheduled for release in 2017. The film is to be written and directed by Michael and Peter Spierig, who are probably best known for Daybreakers (2009), and is to star Helen Mirren.

Although there is necessarily something quite hyper-real about the new crop of Hammer films, it cannot be denied that they continue to look the part in a crowded marketplace hawking a style that the studio itself perfected in the glory days of post-Suez anxiety and the sixties before they swung. Purest may argue that the era of Cushing and Lee and Fisher and Francis cannot easily be matched, but that is the nature of cultural history. There will never be another Elvis or Michael Jackson either. That said, for me, the shades of the great Hammer ensemble could still be glimpsed in Wake Wood, The Quiet Ones and, especially, the original Woman in Black, like spirits gazing out from a mirror. One cannot but hope that they approve.

This is an updated version of an original piece first published in The Wiley-Blackwell Encyclopedia of the Gothic (2012) edited by W. Hughes, D. Punter & A. Smith.

SELECT BIBLIOGRAPHY

Barnes, Alan & Hearne, Marcus. (2007). The Hammer Story. London: Titan.

Chibnall, Steve & Petley, Julian. (2001). British Horror Cinema. London: Routledge.

Cushing, Peter, (1986). Peter Cushing: An Autobiography. London: Weidenfeld and Nicolson.

Eyles, Allen, Adkinson, Robert, & Fry, Nicholas (Eds). (1981). The House of Horror. 2nd ed. London: Lorrimer.

Hutchins, Peter. (1993). Hammer and Beyond: The British Horror Film. Manchester: Manchester University Press.

Hutchinson, Tom. (1974). Horror and Fantasy in the Cinema. London: Studio Vista.

Kinsey, Wayne. (2002). Hammer Films: The Bray Studio Years. London: Reynolds & Hearn.

Kinsey, Wayne. (2007). Hammer Films: The Elstree Studio Years. London: Tomahawk Press.

McCarty, John. (1984). Splatter Movies. London: Columbus.

Meikle, Denis. (1996). A History of Horrors: The Rise and Fall of the House of Hammer. London: Scarcrow Press.

Pirie, David. (2007). A New Heritage of Horror: The English Gothic Cinema. London: I.B. Tauris & Co.

Rigby, Jonathan, (2000). English Gothic: A Century of Horror Cinema. London: Reynolds & Hearn.

Sellar, Maurice. (1987). Best of British: A Celebration of Rank Film Classics. London: Sphere.

Sinclair McKay (2007) A Thing of Unspeakable Horror: The History of Hammer Films. London: Aurum Press.

[…] Source: https://ainsworthandfriends.wordpress.com/2016/06/08/the-house-of-horror-a-history-of-hammer/ […]

[…] Until the 1950s, Britain’s contribution to the horror genre was modest, with few films being produced and being successful. In 1957 Hammer Horror released The Curse of Frankenstein, which was successful, and helped Hammer achieve international success. […]

[…] this sense, the new Dracula more than delivers. Filmed at Bray Studious, the drama’s debt to Hammer is obvious, and there’s a lot of Christopher Lee in Claes Bang’s interpretation of The Count, […]

[…] this sense, the new Dracula more than delivers. Filmed at Bray Studious, the drama’s debt to Hammer is obvious, and there’s a lot of Christopher Lee in Claes Bang’s interpretation of The Count, […]