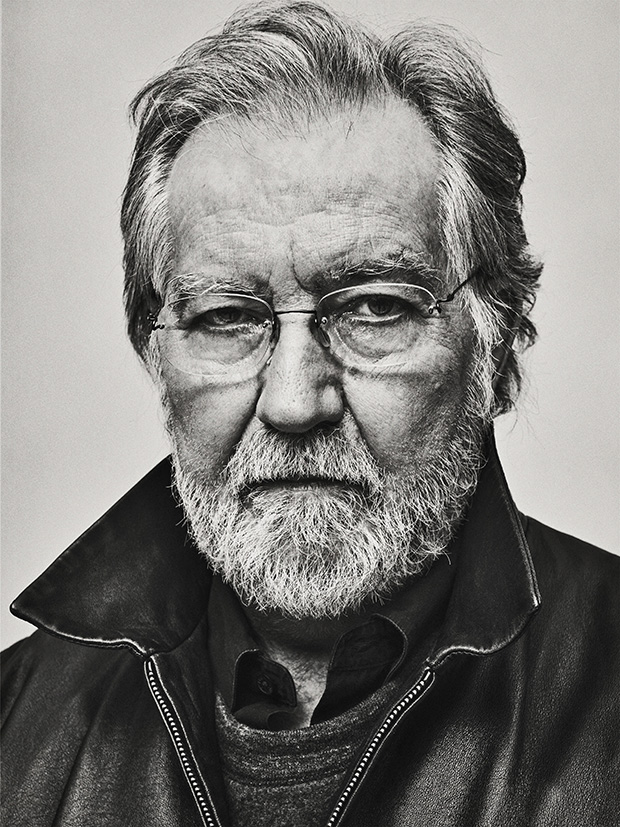

This week, horror fans and old goths like me around the world mourn the passing of Tobe Hooper, who died on Saturday at the age of 74, barely a month-and-a-half after we lost George A. Romero. Few directors get to redefine a genre, but Romero and Hooper both achieved this with Night of the Living Dead (1968) and The Texas Chainsaw Massacre (1974), two utterly ground-breaking movies. As a mark of respect, I’d just like to say a few words about Hooper’s remarkable breakout masterpiece, a film that more than any other sent me down the left-hand path of video nasties, meat movies, and independent horror in the seventies, for which I am eternally grateful.

‘No-one, absolutely no-one ever forgets the first time they ever saw The Texas Chainsaw Massacre’ begins the theatrical trailer for Kim Henkel’s Texas Chainsaw Massacre: The Next Generation (1994). This was a fascinating misfire from Henkel, who co-wrote the original with Hooper when they were fresh out of the University of Texas film school. It starred a very young Renée Zellweger as the final girl, with Matthew McConaughey as one of the chainsaw family (1). This film is an interesting bridge between the first three movies – TCM Parts 1 and 2 (both directed by Hooper) and Jeff Burr’s under-rated Leatherface (1990) – and the franchise reboot that began in 2003 with Marcus Nispel’s excellent remake of the original movie. With the wry humour that characterises the Chainsaw mythos, this trailer placed The Texas Chainsaw Massacre in the collective consciousness of American culture alongside such seismic historical markers as the Kennedy assassination (along with the fall of the Alamo, the other event synonymous with Texas), and the first Moon landing; at the same time hinting at more personal and illicit milestones like your first drink, cigarette, kiss, or even losing your virginity.

‘No-one, absolutely no-one ever forgets the first time they ever saw The Texas Chainsaw Massacre’ begins the theatrical trailer for Kim Henkel’s Texas Chainsaw Massacre: The Next Generation (1994). This was a fascinating misfire from Henkel, who co-wrote the original with Hooper when they were fresh out of the University of Texas film school. It starred a very young Renée Zellweger as the final girl, with Matthew McConaughey as one of the chainsaw family (1). This film is an interesting bridge between the first three movies – TCM Parts 1 and 2 (both directed by Hooper) and Jeff Burr’s under-rated Leatherface (1990) – and the franchise reboot that began in 2003 with Marcus Nispel’s excellent remake of the original movie. With the wry humour that characterises the Chainsaw mythos, this trailer placed The Texas Chainsaw Massacre in the collective consciousness of American culture alongside such seismic historical markers as the Kennedy assassination (along with the fall of the Alamo, the other event synonymous with Texas), and the first Moon landing; at the same time hinting at more personal and illicit milestones like your first drink, cigarette, kiss, or even losing your virginity.

I can certainly still remember my first time. It was a grainy VHS transfer from a US copy, procured under the counter in 1984 from the same guy who sold me I Spit on Your Grave, A Clockwork Orange, and Dawn of the Mummy, films you can now routinely see on television but possession of which back then could get you arrested under the new UK Broadcasting Act. I had ached to see this movie ever since I read the House of Hammer review after its first NFT showing in 1976, and it didn’t disappoint. I get the same rush watching it now, and I still feel a little dirty.

The Texas Chainsaw Massacre was finally granted a general cinema and video release by the British Board of Film Classification twenty-six years after it was made, and this poster child for the Obscene Publications List is now acknowledged as one of the great films of the twentieth century, not just as a genre picture, but a dark work of art. The indie director Jim Van Bebber, for example, said that seeing The Texas Chainsaw Massacre for the first time ‘was as profound a cinematic experience as seeing 8 ½ and Citizen Kane’ (2). In genre terms, any claim regarding this film’s significance is probably an understatement. As the late Chas Balun of Fangoria and Gorezone observed, ‘one relatively infallible way to discern whether self-proclaimed genre experts have their heads up their asses or not is to check out their commentary on Chainsaw. If it’s ignored, merely given a perfunctory nod, or described with any factual errors, well, how can you respect anything else they might say?’ (Balun: 1986, 13). The Texas Chainsaw Massacre can also be viewed historically as the focal point of a particular and mischievous type of post-war American gothic, from the EC horror comics and attendant moral panic of the early 1950s, through Hitchcock’s Psycho and its imitators, to the grand-guignol ‘splatterpunk’ (3) of the 80s, and all the way up to the millennial postmodern revisionism of Scream and The Blair Witch Project and the slick and knowing contemporary carnage of Ash vs. the Evil Dead.

The Texas Chainsaw Massacre was finally granted a general cinema and video release by the British Board of Film Classification twenty-six years after it was made, and this poster child for the Obscene Publications List is now acknowledged as one of the great films of the twentieth century, not just as a genre picture, but a dark work of art. The indie director Jim Van Bebber, for example, said that seeing The Texas Chainsaw Massacre for the first time ‘was as profound a cinematic experience as seeing 8 ½ and Citizen Kane’ (2). In genre terms, any claim regarding this film’s significance is probably an understatement. As the late Chas Balun of Fangoria and Gorezone observed, ‘one relatively infallible way to discern whether self-proclaimed genre experts have their heads up their asses or not is to check out their commentary on Chainsaw. If it’s ignored, merely given a perfunctory nod, or described with any factual errors, well, how can you respect anything else they might say?’ (Balun: 1986, 13). The Texas Chainsaw Massacre can also be viewed historically as the focal point of a particular and mischievous type of post-war American gothic, from the EC horror comics and attendant moral panic of the early 1950s, through Hitchcock’s Psycho and its imitators, to the grand-guignol ‘splatterpunk’ (3) of the 80s, and all the way up to the millennial postmodern revisionism of Scream and The Blair Witch Project and the slick and knowing contemporary carnage of Ash vs. the Evil Dead.

Compared to what followed, eventually arriving on mainstream television in shows like American Horror Story and The Walking Dead, The Texas Chainsaw Massacre is remarkably bloodless. The controversy that once surrounded this film, mostly generated by people that had never seen it, and the gloriously over-the-top tabloid title itself, continues to convey the impression that the film is graphically violent. In fact, it implies much but Hooper, like Hitchcock, shows very little. Nonetheless, this is probably one of the most gruelling, fidgety eighty-five minutes that you will ever spend in front of a screen. William Lustig (director of the thoroughly unpleasant and once banned-in-Britain Maniac, 1980), recalled attending an early screening in 1974 in which ‘The whole cinema bonded into one mass-hysterical group watching this movie that was totally outrageous.’ Then, as the original trailers confidently asserted, the distribution company (Bryanston) elated by the critical acclaim the film initially received from the New York intelligentsia, ‘after you stop screaming, you’ll start talking about it.’ Rex Reed described it as, ‘the most horrifying motion picture I have ever seen. This film is positively ruthless in its attempt to drive you right out of your mind. It accomplishes everything it sets out to do with brilliance and unparalleled terror. This is the horror movie to end them all’ (4). Reed, a fashionable film critic who did not shy away from the avant-garde – see his performance in Myra Breckenridge – understood immediately the significance and device of The Texas Chainsaw Massacre: Hooper’s sense of horror comes from a devastatingly acute perception of the illogic of nightmare and the unreason of madness. Despite popular misconceptions as to the level of stage blood in this film, Hooper wasn’t trying to turn his audience’s stomach or impress them with special effects; he was, as Reed understood, going for their unconscious. As Van Bebber put it:

It wants to hurt you, it just wants to hurt you. Everything is inside it to attack the audience. That is something we don’t find in horror anymore. Everybody wants to shake your hand or meet you halfway and then try and scare you by hiding behind the door. This thing was fucking coming out in clown paint, blood-spattered with homicide on its mind.

As Leslie A. Fielder wrote, ‘the gothic is the product of an explicit aesthetic that replaces the classic concept of nothing-in-excess with the revolutionary doctrine that nothing succeeds like excess’ (Fielder: 1984, 134). The Texas Chainsaw Massacre is designed to drive you crazy, at least for as long as you watch. As the original UK poster art asked its potential audience, ‘Can you survive The Texas Chainsaw Massacre?’ The tag line for the original American poster had been ‘Who will survive, and what will be left of them?’ The UK poster displaces this threat to the victims within the film onto the victims watching it; we are challenged, in effect, to a test of psychological endurance.

While Hooper’s movie shares some similarities with drive-in movies like Jack Hill’s Spider Baby (1967), in which a family of murderous lunatics live in a decaying rural mansion, and the redneck rampage of Harold Daniels’ Poor White Trash (1957), the closest conceptual correlative is George A. Romero’s seminal Night of the Living Dead. Romero’s film brought horror home. It contained no monsters from outer space (so popular at decade previously at the height of the Cold War), and no supernatural beings with creepy Eastern European accents. As the central character of the sequel, Dawn of the Dead (1978), later says of the zombie hoards, ‘They’re us.’ Night of the Living Dead was set in a recognisable American present, the violence was lingering and unsettlingly realistic, the film’s climax nihilistic and inconclusive: the (black) hero, as well as the rest of the principal cast, was dead while the cannibal zombies were still out there and multiplying. John Carpenter – whose Halloween moved the genre forward again in 1978 – said of Romero:

While Hooper’s movie shares some similarities with drive-in movies like Jack Hill’s Spider Baby (1967), in which a family of murderous lunatics live in a decaying rural mansion, and the redneck rampage of Harold Daniels’ Poor White Trash (1957), the closest conceptual correlative is George A. Romero’s seminal Night of the Living Dead. Romero’s film brought horror home. It contained no monsters from outer space (so popular at decade previously at the height of the Cold War), and no supernatural beings with creepy Eastern European accents. As the central character of the sequel, Dawn of the Dead (1978), later says of the zombie hoards, ‘They’re us.’ Night of the Living Dead was set in a recognisable American present, the violence was lingering and unsettlingly realistic, the film’s climax nihilistic and inconclusive: the (black) hero, as well as the rest of the principal cast, was dead while the cannibal zombies were still out there and multiplying. John Carpenter – whose Halloween moved the genre forward again in 1978 – said of Romero:

With Night of the Living Dead, George Romero bought a feel to horror films that had never been seen before. He combined several different elements. One was a documentary feel that came from his use of black-and-white photography and hand-held camera. Secondly, his dealing with graphic violence started an entire trend in horror films. Before that point, horror films were usually about rubber monsters or hands groping in the dark; tremendous clichés that went back to the thirties and forties. George revolutionized that. He made the horror movie something to contend with. His work has influenced every major director in the horror genre since 1968 (qtd. in Gagne: 1987, 21).

Romero and his crew had set a genre precedent which could not be ignored, and those who did ignore it, such as Hammer Films in Great Britain, who continued to make more traditional ‘period’ gothic well into the 70s, went to the wall. Even Roger Corman moved away from his hugely successful ‘Poe Cycle’ starring Vincent Price towards a modern setting. The paradigm shifts quite obviously in Peter Bogdanovich’s Targets (1967). Bogdanovich, one of Corman’s stable of young directors, cast Boris Karloff as an ageing horror star appearing at a retrospective of his own work (from the Corman era naturally), and the narrative contrasts this cosy gothic fiction with the horror of a normal-looking guy who goes home one day and kills his entire family before going on a random rampage with his hunting rifle. The climax takes place at a drive-in theatre showing Corman’s The Terror (1963), the type of gothic narrative which the great man typified giving way to a much more modern trauma which continues to haunt America to this day, the cause of which is often ironically and erroneously laid at the feet of the film makers. Rather poetically, Targets was also Karloff’s swan song.

The Texas Chainsaw Massacre was also preceded by a collaboration between Wes Craven and Sean S. Cunningham (who was to give us the Friday the 13th franchise). The Last House on the Left (1972), based loosely upon Bergman’s The Virgin Spring (1959), features a gang of psychotic criminals (some of whom are related, as in The Texas Chainsaw Massacre), who torture, rape and murder two teenage girls on their way to a concert and then co-incidentally hole-up in the family home of one of their victims. Last House on the Left begins Craven’s preoccupation with the dehumanisation of violence, and with turning ordinary Americans into instruments of vengeance. The same motif can be seen, for example, in his 1977 film The Hills Have Eyes, in which a middle-class family is forced to brutally fight for their lives against a family of mutant cannibals in the Nevada desert. In The Last House on the Left, the besieged parents kill their tormentors every bit as sadistically as the gang had previously treated their daughter and her friend: one character is horribly castrated and left the bleed to death while, notably, their leader, ‘Krug,’ is killed by an outraged father with a chainsaw. The violence was hardcore and this film was banned in Britain for decades. ‘Can a movie go too far?’ was the question posed by the original poster art.

Such was the background to The Texas Chainsaw Massacre at the cutting edge of American new wave cinema. The Summer of Love was over, Charles Manson and the Family were in jail charged with murder, Jim Morrison, Jimi Hendrix, Brian Jones and Janice Joplin were all dead, Nixon was in the Whitehouse, and the Vietnam War raged on (with images of blood and death on the TV news every night). Since Dennis Hopper and Peter Fonda had gone ‘looking for America’ in Easy Rider in 1969, maverick young film-makers were eager to demonstrate that to have the American Dream, you must necessarily also have the American Nightmare. The Texas Chainsaw Massacre is therefore both American gothic and outrageous satire. Kim Henkel, when asked why he created the ‘chainsaw family,’ replied with a smile that he ‘wanted to scare the shit out of someone.’ Hooper has said that, ‘I think what I was trying to say was: This is America!’

Such was the background to The Texas Chainsaw Massacre at the cutting edge of American new wave cinema. The Summer of Love was over, Charles Manson and the Family were in jail charged with murder, Jim Morrison, Jimi Hendrix, Brian Jones and Janice Joplin were all dead, Nixon was in the Whitehouse, and the Vietnam War raged on (with images of blood and death on the TV news every night). Since Dennis Hopper and Peter Fonda had gone ‘looking for America’ in Easy Rider in 1969, maverick young film-makers were eager to demonstrate that to have the American Dream, you must necessarily also have the American Nightmare. The Texas Chainsaw Massacre is therefore both American gothic and outrageous satire. Kim Henkel, when asked why he created the ‘chainsaw family,’ replied with a smile that he ‘wanted to scare the shit out of someone.’ Hooper has said that, ‘I think what I was trying to say was: This is America!’

Hooper and Henkel had already made a movie together. Interestingly, Eggshells (1972) was about the decline of a hippie commune and coming to terms with the end of the sixties. The film won an award at the Atlanta Film Festival that year, but was not widely seen outside the art house circuit. Hooper needed an affordable but commercial project to break into Hollywood, and Night of the Living Dead was obviously inspirational. Exploitation films also had a guaranteed (teenaged drive-in) audience and, like the Expressionist film-makers of the 20s and 30s, Romero had also proved that horror could be art.

Still preoccupied with what we might call the Condition of America question, Hooper seems to have combined this with a childhood memory of Wisconsin relatives coming to visit and telling the tale of the notorious necrophiliac Ed Gein, ‘the woman skinner of Wisconsin,’ a backward and backwoods boy who had taken to robbing graves and wearing and decorating his deserted farmhouse with body parts in the early 1950s, before his insanity inevitably led to murder. His activities were finally discovered in 1957 and he died in the Wisconsin Central State Hospital for the Criminally Insane in 1984. Robert Bloch made no secret of the fact that this case was the inspiration for Psycho, even connecting the stories in the original novel that preceded Hitchcock’s movie in 1959: ‘Some of the write-ups compared it to the Gein affair up North, a few years back. They worked up a sweat over the “house of horror” and tried their damnedest to make out that Norman Bates had been murdering motel visitors for years’ (Bloch: 1962, 119). By the time of American Psycho, Bret Easton Ellis’ yuppie serial killer, Patrick Bateman (named in a nod to Norman Bates), acknowledges Gein as a kind of inspirational folk hero, the father of all American psychos:

After a deliberate pause I say, ‘do you know what Ed Gein said about women?’

‘Ed Gein?’ one of them asks. ‘Maître d’ at Canal Bar?’

‘No,’ I say. ‘Serial Killer, Wisconsin in the fifties. He was an interesting guy.’

‘You’ve always been interested in stuff like that, Bateman,’ Reeves says, and then to Hamlin, ‘Bateman reads those biographies all the time: Ted Bundy and Son of Sam and Fatal Vision and Charlie Manson. All of them.’

‘So what did Ed say?’ Hamlin asks, interested.

‘He said,’ I begin, “When I see a pretty girl walking down the street I think two things. One part of me wants to take her out and be real nice and sweet and treat her right.”’ I stop, finish my J&B in one swallow.

‘What does the other part of him think?’ Hamlin asks tentatively.

‘What her head would look like on a stick,’ I say.

Hamlin and Reeves look at each other and then back at me before I start laughing, and then the two of them uneasily join in (Ellis: 1991, 92).

Deeply sexist, and all at once disturbing and knowingly witty, Ellis has perfectly caught the Gein legend. As for Hooper, who was a pre-schooler when he heard the story: ‘It stuck with me,’ he later said.

In addition to The Texas Chainsaw Massacre, there are several Gein-inspired movies out there, for example William Girdler’s cheap and cheerful Three on a Meathook (1973); the excellent Deranged (1974), co-written and directed by Jeff Gillen and Alan Ormsby, which was unfortunately buried at the box office by The Texas Chainsaw Massacre; Jonathan Demme’s The Silence of the Lambs (1990); and Chuck Parello’s Ed Gein (2000). Gein is to macabre American folklore what ‘Jack the Ripper’ is to English popular history. Just as the Whitechapel killings were interpreted in terms of gothic fiction at the time, the murderer appearing to have walked straight out of the pages of a penny-dreadful (5), Gein, except to the friends and family of his victims, has always seemed more like a character from an EC horror comic than a real human being who had killed at least two women and desecrated the graves of dozens of others.

In addition to The Texas Chainsaw Massacre, there are several Gein-inspired movies out there, for example William Girdler’s cheap and cheerful Three on a Meathook (1973); the excellent Deranged (1974), co-written and directed by Jeff Gillen and Alan Ormsby, which was unfortunately buried at the box office by The Texas Chainsaw Massacre; Jonathan Demme’s The Silence of the Lambs (1990); and Chuck Parello’s Ed Gein (2000). Gein is to macabre American folklore what ‘Jack the Ripper’ is to English popular history. Just as the Whitechapel killings were interpreted in terms of gothic fiction at the time, the murderer appearing to have walked straight out of the pages of a penny-dreadful (5), Gein, except to the friends and family of his victims, has always seemed more like a character from an EC horror comic than a real human being who had killed at least two women and desecrated the graves of dozens of others.

The EC countryside was populated almost entirely by moronic cannibals and psychos. Jack Davies – a native of Atlanta – set his stories in the middle of rural nowhere, playing on the gothic otherness of the South. A ‘typical Jack Davis horror story,’ wrote comics historian Mike Benton, ‘takes place in a backwater village, populated by cretins who appear to be the hairy, pimply offspring of incestuous mating. Flies buzz around, dogs scratch at ticks, and evil – degenerate, perverse evil – pulses, throbs, and swells on every page,’ continuing:

Many of Davis’ EC stories revolve around a character who is either prey or predator. Someone must die so someone can live, and you can bet someone does die, usually in a most horribly satisfying fashion.

Davis drew people naturally ugly. Even his women had overbites and big feet. The atavistic and primal look of the people in a Jack Davis horror story always fit in with the accompanying plots of grim and gritty survival (Benton: 1991, 14 – 15).

In a Jack Davis story, death was always arbitrary. Innocents simply blundered into this in-bred Twilight Zone like butterflies caught in a web. They were killed merely because they were there, because they didn’t understand the rules of the jungle, and because they weren’t from around those parts. Foreshadowing the ‘video nasty’ controversy that saw The Texas Chainsaw Massacre banned in Britain and several other European countries, the hugely popular EC crime and horror titles were shut down by a moral panic engendered by the child psychologist Dr Fredric Wertham. His book, The Seduction of the Innocent: The Influence of Comic Books on Today’s Youth (1954), led to Senate Subcommittee Hearings and the hasty self-regulation of the industry through the Code of the Comics Magazine Association of America, which made distribution of EC comics impossible. Like The Texas Chainsaw Massacre, these comics are now acknowledged as influential genre trailblazers. In his analysis of American Gothic, Danse Macabre (1982), Stephen King cites EC publisher and writer William M. Gaines alongside Edgar Allan Poe in terms of cultural significance. King used the EC device of placing gothic archetypes in a contemporary setting in his second novel, Salem’s Lot (1975), a kind of suburban Nosferatu. Tobe Hooper directed Salem’s Lot for television in 1979, scaring the hell out of everybody.

Hooper is the quintessential heir to the EC aesthetic, especially the work of Jack Davis. ‘I started reading [EC comics] when I was about seven,’ he told Cinefantastique in 1977:

They were absolutely frightening, unbelievably gruesome. And they were packed with the most unspeakably horrible monsters and fiends, most of which specialised in mutilation … I loved them. They were not in any way based on logic. To enjoy them you had to accept that there was a bogey man out there … Since I started reading these comics when I was young and impressionable, their overall feeling stayed with me. I’d say they were the single most important influence on The Texas Chainsaw Massacre. A lot of their mood went into the film (qtd. in Jaworzyn: 2003, 30).

In concept, character and controversy, Hooper’s meat movie masterpiece was pure EC, and his next movie, Death Trap (AKA Eaten Alive, 1976), was based on a story by Davis called ‘Country Clubbing’ (Haunt of Fear 23). Hooper lit from a comic book palette, while his vérité style recalled the intimate perspective of EC narratives, as did his relentless parodies of the American family. There was also a common preoccupation with cannibalism, necrophilia and putrefaction. In Poltergeist (1982), Hooper also blended the Twilight Zone story ‘Little Girl Lost’ with the Vault of Horror story ‘Graft in Concrete’ (again by Jack Davis, from Vault of Horror 15); and when EC’s flagship title, Tales from the Crypt, finally returned with a vengeance as an HBO television series, Tobe Hooper directed the episode ‘Dead Wait’ in 1991.

Hooper begins his assault on his audience in a very direct way. The Texas Chainsaw Massacre opens with a brief, journalistic prologue stating, as did the posters and trailers, that this was a true story (which it wasn’t) (6). This quasi-documentary, cinéma-vérité sensibility pervades the entire film, emphasised by the use of hand-held cameras and actually assisted by the low production values. The terribly serious narrator was John Larroquette of the TV show Night Court, his (then) instantly recognisable voice a cultural code which immediately introduced the director’s central device: a mixture of verisimilitude and showmanship in roughly equal measure.

The film proper begins with darkness and digging. We hear laboured breathing, scraping sounds suggesting exhumation punctuated by the periodic flash of a camera (accompanied by one of Wayne Bell’s weird sound effects); each flash briefly illuminates a close up of part a badly decomposed human body. The camera tracks back out of the darkness (accompanied by atonal sounds using, according to Hooper, a variety of Oriental instruments and children’s toys), to reveal a very rotten male corpse wired to a monument in a graveyard in the baking Sun like a da da sculpture in hell. A radio news broadcast can be heard to report that ‘Grave robbing in Texas is this hour’s top story. Acting on a tip-off, members of the county sheriff’s office went to a cemetery just outside the small rural Texas community of Newt. Officers there discovered what appeared to be a grisly work of art … Subsequent investigation has revealed at least a dozen empty crypts and it is feared more will turn up as the probe continues’ (7). Then the title appears and the credits roll against a negative image of Sun spots flaring away into space, Hooper and Bell’s jangling, experimental music and the nasty news report. The next shot begins with a close-up of a surrealist road kill (a squashed armadillo), and a Volkswagen Microbus drives into shot through the shimmering heat haze. Traffic noise partially obscures the radio report, so that only snippets of death and disaster can be heard:

A sixteen storey building in downtown Atlanta collapsed yesterday killing at least twenty-nine people … Police in Gary, Indiana have been unable to identify the bodies of a young man and woman discovered by children … Police in Dallas arrested a young couple today. Complaints by neighbours led them to discover the eighteen-month-old daughter of the couple chained in the attic of a dilapidated house…

This is followed by some cheery country music and move to the interior of the van. The occupants (two square-jawed, slightly hairy guys in jeans with two pretty girls) are straight out of Scooby-Doo (as is the van), only they have a fat boy, Franklin (Paul A. Partain), in a wheelchair instead of Scooby. One of the girls (Pam, played by Teri McMinn, who has since completely disowned her part in the film), is reading aloud from American Astrology magazine: ‘The condition of retrogradation is contrary or inharmonious to the regular direction of actual movement in the Zodiac, and is in that respect evil. Hence, when malefic planets are in retrograde – and Saturn’s malefic – their malevolence is increased … Saturn’s a bad influence, and it’s particularly bad now because it’s in retrograde.’ This function as an ominous and personalised continuation of the radio commentary, and is equally naturalistic. The effect is cumulative. You feel uneasy, you can still smell the graveyard, the hype has already got you nervous and the opening titles were horrible.

There was nothing like this in 1974, and cinema audiences had yet to become inured to the special make-up effects of Tom Savini and Rick Baker; there was no Jason, Freddy or The Walking Dead with which to cross reference the imagery. Neither could the audience appeal to the traditional gothic; this was gritty and modern and close.

The group visits the graveyard, partly because Franklin’s sister Sally (Marilyn Burns) is concerned their grandfather’s grave has been disturbed, but mostly out of morbid curiosity, notably placing them in the same point of view as the film’s audience. The road trip then becomes even more ominous as the van passes ‘the old slaughterhouse’ (with a fast-cut to stupid-looking, drooling cows crammed together), which is announced by its stench. Franklin describes the different methods of slaughtering cattle, from the sledgehammer to the ‘humane killer,’ also doing the sound effects. For about twenty minutes now, the film has assaulted us with an audio-visual montage of sweaty images of death and decay. Hooper rubs our noses in it: he laughs at our collective fear of death, and juxtaposes the apparently carefree lives of the middle-class teens (the demographic that would make up much of his audience), with the ever-present and random injustices of madness (the grave robber/sculptor), and death (the grave itself); the radio news report covers both cases. The experience also seems voyeuristic, illicit, the realism pornographic. If anyone laughs when Franklin falls down or starts whinging on about something, it is an uneasy, guilty laughter. You ask yourself: How far is this director going to go?

The group visits the graveyard, partly because Franklin’s sister Sally (Marilyn Burns) is concerned their grandfather’s grave has been disturbed, but mostly out of morbid curiosity, notably placing them in the same point of view as the film’s audience. The road trip then becomes even more ominous as the van passes ‘the old slaughterhouse’ (with a fast-cut to stupid-looking, drooling cows crammed together), which is announced by its stench. Franklin describes the different methods of slaughtering cattle, from the sledgehammer to the ‘humane killer,’ also doing the sound effects. For about twenty minutes now, the film has assaulted us with an audio-visual montage of sweaty images of death and decay. Hooper rubs our noses in it: he laughs at our collective fear of death, and juxtaposes the apparently carefree lives of the middle-class teens (the demographic that would make up much of his audience), with the ever-present and random injustices of madness (the grave robber/sculptor), and death (the grave itself); the radio news report covers both cases. The experience also seems voyeuristic, illicit, the realism pornographic. If anyone laughs when Franklin falls down or starts whinging on about something, it is an uneasy, guilty laughter. You ask yourself: How far is this director going to go?

The first act closes when the gang stops to pick up a hitchhiker by the slaughterhouse, masterfully played by Ed Neal. He looks like a Jack Davis character. With greasy skin, lank hair, huge, purple facial birthmark, a pouch round his neck that looks like a mule-stomped gopher and wearing khaki fatigues, the crazed working-class Vietnam vet confronts the middle-class college Love Generation. ‘I think we just picked up Dracula,’ says Franklin, bringing the old and new gothic together. ‘I have a knife,’ the hitcher announces at one point, pulling a rusty straight razor out of his boot proudly, ‘it’s a good knife.’ ‘I’m sure it is man,’ replies Kirk (William Vail), one of the boyfriends, shakily. In common with the majority of the audience, Kirk is totally unequipped emotionally or physically to deal with this type of situation.

From this point on, the pace of the narrative continues to accelerate until you slump back in your seat, exhausted and relieved, when the film ends about an hour later, and everyone in the van except Sally is dead. They are all murdered by Leatherface, a drooling simpleton in a mask made of human skin, doing exactly what he used to do in the slaughterhouse, killing with a sledgehammer then carving up the carcass with a chainsaw, his signature weapon. He is supported and enabled by his brother (the hitcher), the ‘cook’ (played by Jim Siedow like a passive-aggressive Mr. Rogers), who is either his father or older brother or both, and their ancient grandpa (who looks dead but isn’t), and their dead but inexpertly preserved grandmother, a symbol of the exhumed mothers of Ed Gein and Norman Bates.

As William Vail, now a set decorator, has said, the family house itself ‘was another character in the movie.’ Just outside Austin, the house was a Victorian Carpenter’s Gothic designed by the architect George Franklin Barber. The look of the house in the movie (now, oddly, a restaurant), and the bone furniture and skin masks were all the work of art director Robert A. Burns, who collected a bewildering amount of body parts and bones – some animal, some human, some real, some not – to produce what Hooper later described as ‘dead art,’ years before Damien Hirst hit the scene. Marilyn Burns said of acting in the house, ‘It was just like the family should live there. Already when you walked in you felt uncomfortable, itchy – you didn’t want to touch anything.’ The old, dark house is, of course, a traditional, gothic space, but an EC correlative would be a Jack Davis story entitled ‘The Death of Some Salesmen’ from Haunt of Fear 15 (1952), in which a commercial traveller is killed by his own product, the ‘handy-dandy meat slicer,’ by the occupants of a remote farmhouse.

The ‘chainsaw house’ also references the Ed Gein case, and a particular dimension of its inhabitant’s psychosis that Hitchcock decided only to hint at with Norman Bates’ penchant for taxidermy. From interviews and police records, Paul Anthony Woods reconstructed the interior of Gein’s isolated farmhouse as discovered by Wisconsin lawmen:

The ‘chainsaw house’ also references the Ed Gein case, and a particular dimension of its inhabitant’s psychosis that Hitchcock decided only to hint at with Norman Bates’ penchant for taxidermy. From interviews and police records, Paul Anthony Woods reconstructed the interior of Gein’s isolated farmhouse as discovered by Wisconsin lawmen:

On the living room wall, they shone a light on a cheap old picture of Jesus, gazing up at Angel Gabriel. A pile of old children’s books on the floor stood next to a copy of Gray’s Anatomy. Then there were the skulls in the Summer kitchen, and the cardboard box in the main kitchen, where a disgusted patrolman had found a collection of gristly, peeling noses.

The furniture removal guy had felt faint as he gripped Ed’s dining room chairs, touching his hand into greasy, lumpy fat – upholstered with human flesh, every one of them. He couldn’t even sit down and recompose himself.

The lamp shades were fashioned from thin, dermatitic skin. The wastebasket was made from a human bread basket. A hunting knife’s sheath was so organic, it was most like a dead guy’s pecker. A Quaker oats box was full of decaying head integument.

‘Oh, what in God’s name is this?’ hollered a visiting captain from Wautoma, too sickened to take in what he was seeing anymore (Woods: 1995, 86).

Horror piled upon horror; the Holocaust image of furniture upholstered in skin is a particularly disturbing comment on the human condition. Gein, however, always denied cannibalism. ‘Eating flesh and drinking blood, I never felt capable of doing that,’ he said in a statement to Chief Detective Weber of the La Crosse PD, ‘That’s kind of a Catholic thing, isn’t it? I don’t think my mother would have approved’ (qtd. in Woods: 1995, 81). Augusta Gein was of strict German Lutheran stock, so grave-robbing and murder would still have been preferable to idolatry. This is similarly the kind of warped logic that characterises the coal-black humour of both EC comics and the low-budget horror film, and one cannot help but compare the photographs of Gein, lazy-eyed and invariably wearing a greasy hunting cap, with the fictional universes of Jack Davis and Tobe Hooper.

With his three generations of inbred maniacs, Hooper is also very much satirising the institution of the American nuclear family. ‘I’ve seen more dysfunction and more hell in families than I would like to have,’ he has said, ‘So I kinda always wanted to do something about a dysfunctional family.’ The negation of family values is completed in his camp follow-through to the original film, when Leatherface, now in an adolescent phase, falls in love and brings a terrified girl he was supposed to kill home for dinner. The cook is outraged, and in another ridiculous inversion swaps the roles of predator and prey by demanding that the girl should ‘Leave him alone damn it!’ Bubba then has the facts of life explained to him by dad, who snatches the chainsaw from his hands when he refuses to ‘finish’ the girl: ‘You have to choose boy,’ he says, ‘sex or the saw. Sex is, well nobody knows, but the saw is family!’ Shaking his head sadly, he concludes, ‘Wait ’til your grandpa hears about this.’ As Robin Wood has written, ‘They are held together – and torn apart – by bonds and tensions with which we are all familiar – with which, indeed, we are likely to have grown up. We cannot clearly dissociate ourselves from them’ (Wood: 1978, 30). Each member of the chainsaw family has an identifiable role and rationale. The hitchhiker is the scavenger who also finds potential victims/food; Leatherface is the family killer, his sexual ambivalence and cross-dressing also making him mother; the older man, the father-figure, is the cook and bread-winner (he runs a gas station) and all three are the carers of Grandpa, the aged, infantile and infirm head of the family, of whom they are all still in awe, as one so often is of an aging patriarch.

It is therefore no surprise that both of Hooper’s chainsaw films culminate around the dinner table. The ordeal of the final girl, Sally, comes to a head in the demented dining room, a scene of dread for many of us at Christmas and Thanksgiving. The negation takes us beyond the Mad Hatter’s tea party; this (to borrow a title from another drive-in movie), is Alice in Acidland. There’s that armadillo again, proudly collected and displayed on the table. The centrepiece of a human pelvis and some sort of table ornament made out of a dead chicken. Everyone is shouting and screaming. Food (all meat, sausages and burgers), is on the table. Leatherface now has on a third face (slightly rouged, a scene where he applies makeup was cut, but re-done by Henkel in TCM: The Next Generation), and a black, ‘Sunday-go-to-meeting’ suit. The cook and the hitcher are locked in an Oedipal struggle, constantly bickering and fighting for control. Sally cries, she screams, she pleads; they mimic and tease: ‘Please,’ she begs (in an awful moment of complete surrender), ‘I’ll do anything.’ Hooper uncomfortably emphasises her distress with extreme close-ups of her very bloodshot eye.

‘There’s no need to torture the poor girl,’ says the cook, calling for the boys to put her out of her misery. But torture is, of course, what this scene is all about, and the film was originally denied certification by the BBFC on the grounds of ‘psychological torture.’ This refers to Sally’s ordeal, but it could equally apply to the audience. James Ferman, the formidable Director of the BBFC from 1974 to 1998, described Sally’s torments as the ‘pornography of terror.’ Ferman admitted he could not identify a single, unacceptable scene that might be cut in order to make the film ‘suitable’ for general release, but found the cumulative effect of the complete text to be too frenzied and offensive. He therefore cut the entire film.

‘There’s no need to torture the poor girl,’ says the cook, calling for the boys to put her out of her misery. But torture is, of course, what this scene is all about, and the film was originally denied certification by the BBFC on the grounds of ‘psychological torture.’ This refers to Sally’s ordeal, but it could equally apply to the audience. James Ferman, the formidable Director of the BBFC from 1974 to 1998, described Sally’s torments as the ‘pornography of terror.’ Ferman admitted he could not identify a single, unacceptable scene that might be cut in order to make the film ‘suitable’ for general release, but found the cumulative effect of the complete text to be too frenzied and offensive. He therefore cut the entire film.

The dinner scene reaches a climax when the family decide that the mummified Grandpa should kill Sally. ‘Now don’t you cry none,’ says the cook. ‘Grandpa’s the best there is. It won’t hurt a bit.’ He sounds as if he’s talking to a child at the dentist’s (8).

What follows is some very black humour indeed. A tin bath is fetched to keep blood off the carpet, and Sally’s head is held over it while Grandpa tries to bash her with a sledgehammer, which keeps dropping out of his palsied fingers and clattering into the bath as the boys get increasingly worked up. The general mayhem allows Sally to escape, and after an agonising chase in which Sally is rescued by a passing motorist and the hitcher is run over by an eighteen-wheeler. Cheated of his prey, Leatherface’s narrative very abruptly concludes, and he is left pirouetting around his chainsaw. The film ends at this point. In common with Night of the Living Dead, the film’s principle killer is still at large. Although Sally has escaped in body, her increasingly deranged laughter in the final shot strongly suggests that her mind is not ever coming back from this nightmare; an impression confirmed by the introductory links to subsequent chainsaw sequels. The Texas Chainsaw Massacre Part 2 describes her as ‘catatonic,’ and by the start of Leatherface: Texas Chainsaw Massacre III she’s already died ‘in a private health care facility.’

At the end of the movie, it’s difficult to know whether to laugh or cry.

The conventional wisdom is that in The Texas Chainsaw Massacre we are witnessing the birth of the modern ‘slasher movie,’ complete with masked psychos and final girls. Even the academic Carol J. Clover initially adopts this position, although noting that The Texas Chainsaw Massacre is ‘an exceptional case,’ citing the polarised nature of the critical debate surrounding the film. ‘At the bottom of the horror heap,’ writes Clover, ‘lies the slasher (or splatter or shocker or stalker) film: the immensely generative story of a psycho killer who slashes to death a string of mostly female victims, one by one, until he is subdued or killed, usually by the one girl who has survived’ (Clover: 1992, 21). Hitchcock’s Psycho is generally accepted as the ancestor of this sub-genre, and the hugely popular Friday the 13th series is the perfect example of the product. When the ‘star’ of this series, Jason Voorhees, supernatural psycho, meets the chainsaw family in the Topps Jason Versus Leatherface comic, the cook whispers to Jason that, ‘I can’t tell you how happy I am to see you an’ Leatherface hittin’ it off! I can tell by lookin’ at you y’all have, you know, lots in common!’ (Imhoff and Collins, 1995). This would seem to be the opinion held by the majority of chainsaw fans around the world judging by the Internet traffic. The character is even to be found in a series of action figures from McFarlane Toys collectively entitled ‘Movie Maniacs,’ Leatherface placed proudly alongside Jason, Freddy Kruger, Michael Myres, and ‘Ghost Face’ from Wes Craven’s Scream. As early as 1978, Robin Wood wrote that ‘Watching The Texas Chainsaw Massacre with a half-stoned audience who cheered every outrage was a terrifying experience’ (Woods: 1978, 32), and I met some very creepy people back in the day collecting obscure and illegal videos.

But beyond the iconography of the mask and the power tool, the similarity between Hooper’s creation and his successors is rather superficial. Jason and his peers have been rendered increasingly bland by a generation of almost identical films that rely on high body counts and technical spectacle to sell tickets. Talking to Darkside Magazine in April 1993, Adam Marcus, the director of Jason Goes to Hell: The Final Friday, explained that ‘This movie is just Jaws. Jason is the shark waiting to eat teenager’s legs off. That’s his only purpose.’ Faced with such a low concept, genre journalists were often reduced to simply listing effects, as in this review of the video re-issue of Friday the 13th Part VI: Jason Lives (1986) in Darkside, December 1990: ‘The body count is as follows: machete for two, impaling on a spear, broken bottle in throat, 360-degree head twist, bare fist through stomach, and assorted stabbings and decapitations.’ As clinical as pornography, and similarly tedious, this is why Wes Craven’s deconstructive Scream was hailed as such a masterpiece, although the subsequent sequels have undermined its original credibility. Jason and friends are much more the product of the European horror tradition than the American, specifically Italian Giallo (literally ‘yellow,’ from the colour of the covers of 1930s pulp novels). This can be easily confirmed by comparing the Friday the 13th series to Blood and Black Lace (1964), and Bay of Blood (1971) by Mario Bava, the only difference being the lack of gothic style that the Italians so effortlessly seem to bring to their film-making. The American popular gothic tradition is much more dominant in The Texas Chainsaw Massacre.

But beyond the iconography of the mask and the power tool, the similarity between Hooper’s creation and his successors is rather superficial. Jason and his peers have been rendered increasingly bland by a generation of almost identical films that rely on high body counts and technical spectacle to sell tickets. Talking to Darkside Magazine in April 1993, Adam Marcus, the director of Jason Goes to Hell: The Final Friday, explained that ‘This movie is just Jaws. Jason is the shark waiting to eat teenager’s legs off. That’s his only purpose.’ Faced with such a low concept, genre journalists were often reduced to simply listing effects, as in this review of the video re-issue of Friday the 13th Part VI: Jason Lives (1986) in Darkside, December 1990: ‘The body count is as follows: machete for two, impaling on a spear, broken bottle in throat, 360-degree head twist, bare fist through stomach, and assorted stabbings and decapitations.’ As clinical as pornography, and similarly tedious, this is why Wes Craven’s deconstructive Scream was hailed as such a masterpiece, although the subsequent sequels have undermined its original credibility. Jason and friends are much more the product of the European horror tradition than the American, specifically Italian Giallo (literally ‘yellow,’ from the colour of the covers of 1930s pulp novels). This can be easily confirmed by comparing the Friday the 13th series to Blood and Black Lace (1964), and Bay of Blood (1971) by Mario Bava, the only difference being the lack of gothic style that the Italians so effortlessly seem to bring to their film-making. The American popular gothic tradition is much more dominant in The Texas Chainsaw Massacre.

In a Cinefantastique piece entitled ‘Stories of Childhood and Chainsaws,’ Mikita Brottman has also convincingly argued that Hooper’s film inverts the rather conservative conventions of the fairy tale:

In fairy tales, this kind of terrible punishment is not a deterrent to crime so much as a means of persuading the child that crime does not pay. Morality is promoted not through the fact that virtue always wins out in the end, but because the bad person always loses and because the hero is most attractive to the child. In CHAINSAW, however, humanity is completely powerless, and the annihilation is complete. There are no heroes or heroines, only victims and villains. In this fairy tale there are no clues, no magic passwords, no treasures to rescue or battles to fight because this is not a narrative governed by any logical order. Neither victims nor slaughterers have any kind of control over themselves or each other, and this lack of control is cosmic and universal. Malevolent predictions come true, suggesting that our defence against horror is finally subject to the forces of arbitrary fate. CHAINSAW is perhaps one of the only stories of true horror that our culture has ever produced. The film’s narrative disorder, illogical sequences of action and apocalyptic sense of destruction are ritualistic, but without the regenerative or collective functions generally associated with ritualised violence. A fairy tale which misleads, bewilders, confuses and ultimately delivers the expectation of defeat is a dangerous story indeed (Brottman, 1996, 40).

In Brottman’s reading, all the traditional elements of fairy tale are present in TCM: elemental imagery; totemism; the house in the woods; lost children; cannibalism; grandparents; sacks and axes; bodily dismemberment; even broomsticks; and the final escape from the forest into the sunshine, to which each is traditionally ascribed, in Jungian terms, universal meaning. But, he argues, Hooper ‘inverts this mythic order and upsets the ritual narrative script – and on a cosmic level’ (Brottman, 1996, 41). A point worth adding to this elegant analysis is the obvious fun that Hooper is having with fairy tale archetypes, as the closest that Brottman gets to addressing his black comedy and slapstick humour is an identification of ‘hints of anarchy and disorder’ (Brottman, 1996, 40). In his follow-through to The Texas Chainsaw Massacre for example, Death Trap (AKA Eaten Alive, 1976), the relationship between the killer, ‘Judd,’ his ‘pet’ alligator and Peter Pan is quite hilariously explicit, his artificial leg surfacing in the water at the end of the film. (Gunnar Hansen, the original Leatherface, has suggested that in this character ‘what you’re really watching is the cook having escaped into the marshes of Louisiana.’)

In Brottman’s reading, all the traditional elements of fairy tale are present in TCM: elemental imagery; totemism; the house in the woods; lost children; cannibalism; grandparents; sacks and axes; bodily dismemberment; even broomsticks; and the final escape from the forest into the sunshine, to which each is traditionally ascribed, in Jungian terms, universal meaning. But, he argues, Hooper ‘inverts this mythic order and upsets the ritual narrative script – and on a cosmic level’ (Brottman, 1996, 41). A point worth adding to this elegant analysis is the obvious fun that Hooper is having with fairy tale archetypes, as the closest that Brottman gets to addressing his black comedy and slapstick humour is an identification of ‘hints of anarchy and disorder’ (Brottman, 1996, 40). In his follow-through to The Texas Chainsaw Massacre for example, Death Trap (AKA Eaten Alive, 1976), the relationship between the killer, ‘Judd,’ his ‘pet’ alligator and Peter Pan is quite hilariously explicit, his artificial leg surfacing in the water at the end of the film. (Gunnar Hansen, the original Leatherface, has suggested that in this character ‘what you’re really watching is the cook having escaped into the marshes of Louisiana.’)

Hooper, like James Whale, who often lamented the overlooked humour of The Bride of Frankenstein (1934), has repeatedly bemoaned the fact that nobody saw the funny side: ‘I brooded for years that no-one appreciated or saw the humour or the comedy of Chainsaw,’ he told David Gregory, elaborating for Empire that, ‘Chainsaw got me identified with the horror genre. People who were willing to give me larger sums of money to make films knew that I had already proven myself in the horror genre. In fact, comedy is the thing I really love’ (qtd. in Collis, 2000). Hence his camp, carnivalesque, satiric and self-referential sequel, Texas Chainsaw Massacre 2 (1986), for which the hardcore fans have never forgiven him: ‘This time around,’ complains the Arrow in the Head review of the 2000 DVD release, ‘the crazy family is no longer real and brutal. They have become the Three Stooges,’ thereby getting the point and totally missing it simultaneously (Fallon, 2000).

The joke was equally lost on the BBFC, who banned it, probably because of the mystique surrounding the title; the multiple Academy Award winner, The Silence of the Lambs, is considerably more violent. (Clover notes that such films tend to be classified as ‘horror’ if low-budget, and ‘drama’ or ‘thriller’ if production values are high.) As Mark Kermode concludes his Time Out Film Guide entry on The Texas Chainsaw Massacre Part 2, ‘Isn’t it about time the censors developed a sense of humour?’ (Kermode: 1999, 900). There is again a very obvious EC connection here, in the form of ‘The Old Witch’s Grim Fairy Tales’ from Haunt of Fear. In a story entitled ‘Marriage Vows’ for example, the recognisable fairy tale dilemma of who should get Princess Buttercup’s hand in marriage is resolved by King Blackheart getting her hand and Prince Dashing the rest of her body (Haunt of Fear 15, 1952).

The joke was equally lost on the BBFC, who banned it, probably because of the mystique surrounding the title; the multiple Academy Award winner, The Silence of the Lambs, is considerably more violent. (Clover notes that such films tend to be classified as ‘horror’ if low-budget, and ‘drama’ or ‘thriller’ if production values are high.) As Mark Kermode concludes his Time Out Film Guide entry on The Texas Chainsaw Massacre Part 2, ‘Isn’t it about time the censors developed a sense of humour?’ (Kermode: 1999, 900). There is again a very obvious EC connection here, in the form of ‘The Old Witch’s Grim Fairy Tales’ from Haunt of Fear. In a story entitled ‘Marriage Vows’ for example, the recognisable fairy tale dilemma of who should get Princess Buttercup’s hand in marriage is resolved by King Blackheart getting her hand and Prince Dashing the rest of her body (Haunt of Fear 15, 1952).

Although the EC dimension is a strong one, there is also a strong ‘true crime’/docu-drama element to Hooper’s film which also belongs to the American gothic tradition: ‘America’s most bizarre and brutal crimes!’ screamed the original ad campaign; ‘What happened was true … This is the motion picture that is just as real, just as close, just as terrifying as being there,’ said the theatrical trailer; ‘It happened!’ added the UK poster, all of which was hype and nonsense. This advertising approach does however demonstrate the film’s allegiance to not only the Gein case and news’ stand pulp, but to an influential work of post-war American literature, Truman Capote’s In Cold Blood: A True Account of a Multiple Murder and Its Consequences (1965).

In Cold Blood is an early example of New Journalism, an experimental attempt to establish a new literary form which the author designated the ‘non-fiction novel,’ combining the thoroughness of journalism with the cunning of a novelist. Taking his inspiration from an actual, and apparently motiveless mass-murder, Capote documented the case/story of two disturbed petty thieves, who wipe out an entire family for $40 in change, with a forensic attention to detail. Whether consciously or not, Capote follows the model bequeathed both by Bloch and Hitchcock in first the novel, and then the film version, of Psycho. Unlike the deliberately mad and ambivalent ‘end’ of The Texas Chainsaw Massacre, Robert Bloch, on both the page and the screen, devotes considerable time and energy to explaining everything in terms of Freudian psychoanalysis, much in the manner that Mrs Radcliffe clarifies the ‘Black Veil’ incident at the conclusion of her seminal gothic novel The Mysteries of Udolpho (1794). Lila Crane (the sister of Mary/Marion, the Janet Leigh character), like most Americans in the Functionalist fifties easily impressed by psychiatrists, concludes in the original novel that, ‘I can’t even hate Bates for what he did. He must have suffered more than any of us. In a way, I can almost understand. We’re all not quite as sane as we pretend to be’ (Bloch: 1962, 125). Capote arrives at the same conclusion by accident rather than design. He similarly unpicks the psychopathology of the homicidal drifters, Perry Smith and Dick Hickock, offering a dizzying array of evidence and analysis ranging from long, psychiatric reports (like Bloch), forensic evidence, school reports, and interviews, to confessional statements. Like the radio report which heralds The Texas Chainsaw Massacre, In Cold Blood concludes with a list of atrocities perpetrated by otherwise quite ordinary folk, such as the other inhabitants of ‘the Corner’ (Death Row), where Perry and Dick are finally incarcerated: Earl Wilson (condemned for the kidnapping, rape and torture of a young girl); Bobby Joe Spencer (murderer); and Lowell Lee Andrews (killed his whole family); he also describes the cross-country murder spree of two young soldiers. The terrible irony is that the more obsessively the author tries to understand such motiveless mayhem, the more psuedo-scientific analysis he brings to bear, the more edgily apparent it becomes that anyone can be a killer: ‘It’s easy to kill,’ says Perry tells an army buddy towards the end, ‘I only knew the Clutters maybe an hour. If I’d really known them, I guess I’d feel different. I don’t think I could live with myself. But the way it was, it was like picking off targets in a shooting gallery’ (Capote: 1966, 239). If this is, in part at least, also the meaning of The Texas Chainsaw Massacre (that it has no meaning), then it is presented not with the deathly seriousness of a psychiatric evaluation, a post-modern novel or even a conspiracy theory, but as some great cosmic joke. Sally may spend most of the film screaming, but she’s laughing at the end.

Such ghastly laughter leads us back to Jim Van Bebber’s analogy of the ‘clown paint,’ of Lon Chaney Snr’s famous metaphor of the clown at midnight, and the dark theatricality which informs the popular gothic. This can be seen repeatedly in the music of Alice Cooper, Marilyn Manson, Rob Zombie, and The Cramps, all made-up and specialising in grand-guignol stage shows, as well as horror comics, grindhouse movies, The Joker and Harley, and the Ed Gein cottage industry: America’s favourite serial killer even has his own international fan club.

It is the ghost of Ed Gein (the authentic ‘Leatherface’), that rightly or wrongly brings everything together. Dead but not forgotten since 1984, he has ceased to be ‘real’ in any meaningful sense. He is now hyper-real. As his biographer has written, ‘The simple truth is that Ed Gein is now as much part of the folklore of many young people as Santa Claus was when they were small. Howls of protestation about how unhealthy it all is will do no good … In this age of random slaughter, we use Ed Gein for light entertainment’ (Woods: 1995, 163 – 4). There was even an underground comic, very much in the EC tradition, which devoted a cover story to Gein. The cover of Weird Trips 2, drawn by William Stout, shows Gein in his trademark hunting cap cooking up a mess of human headcheese and conspiratorially inviting the potential buyer to join him ‘for some vittles.’ If you look closely at the faces nailed to the wall in the background, you can see the ‘Old Witch’ from EC’s Haunt of Fear and Tobe Hooper’s Leatherface. The image is, as once were its component parts, transgressive – that being the political key to underground art. But beyond that, as the lonely and pathetic shade of Ed Gein finds his place in the world at last, there is something almost reassuringly familiar about such childhood monsters and, beyond that, there is the big joke, the last laugh.

It is the ghost of Ed Gein (the authentic ‘Leatherface’), that rightly or wrongly brings everything together. Dead but not forgotten since 1984, he has ceased to be ‘real’ in any meaningful sense. He is now hyper-real. As his biographer has written, ‘The simple truth is that Ed Gein is now as much part of the folklore of many young people as Santa Claus was when they were small. Howls of protestation about how unhealthy it all is will do no good … In this age of random slaughter, we use Ed Gein for light entertainment’ (Woods: 1995, 163 – 4). There was even an underground comic, very much in the EC tradition, which devoted a cover story to Gein. The cover of Weird Trips 2, drawn by William Stout, shows Gein in his trademark hunting cap cooking up a mess of human headcheese and conspiratorially inviting the potential buyer to join him ‘for some vittles.’ If you look closely at the faces nailed to the wall in the background, you can see the ‘Old Witch’ from EC’s Haunt of Fear and Tobe Hooper’s Leatherface. The image is, as once were its component parts, transgressive – that being the political key to underground art. But beyond that, as the lonely and pathetic shade of Ed Gein finds his place in the world at last, there is something almost reassuringly familiar about such childhood monsters and, beyond that, there is the big joke, the last laugh.

This is what headcheese and chainsaws is all about. Whether you find it funny or not is up to you to decide. As for me, well, my family’s always been in meat…

In Memory of William Tobe Hooper (January 25, 1943 – August 26, 2017)

NOTES

- See also the original Leatherface (1990), in which Viggo Mortensen played one of the murderous family, Eddie ‘Tex’ Sawyer.

- Quoted from the excellent documentary The Texas Chainsaw Massacre: The Shocking Truth. David Gregory. Blue Underground, 2000. Unless otherwise stated, subsequent interview quotations are taken from this film.

- A term allegedly coined by David J. Schow, an interesting and influential horror writer whose film credits include The Crow (1994) and, notably, Leatherface: Texas Chainsaw Massacre III (1990).

- Quoted from the original theatrical trailer to The Texas Chainsaw Massacre.

- ‘One may search the ghastliest efforts of fiction and fail to find anything to surpass these crimes in diabolical audacity. The mind travels back to the pages of DE QUINCEY for an equal display of scientific delight in the details of butchery; or EDGAR ALLAN POE’S “Murders in the Rue Morgue” recur in the endeavour to conjure up some parallel for this murderer’s brutish savagery.’ The London Times September 10, 1888, on the murder of Annie Chapman. W.T. Stead, in his article for the Pall Mall Gazette ‘Murder and More to Follow,’ invoked The Strange Case of Dr Jekyll and Mr Hyde as a psychological profile of the killer. Richard Mansfield’s portrayal of Stevenson’s character in the West End was also considered so convincing that some enterprising journalists put him forward as a suspect, causing the production to be closed.

- This opening is parodied in David Gregory’s documentary, where it is suggested that the cast and crew suffered just as much as Sally and her friends.

- The Texas Chainsaw Massacre. Dir Tobe Hooper. Perf. Marilyn Burns, Edwin Neal, Jim Siedow, and Gunnar Hansen. Vortex, 1974. All quotations are taken from the 1999 Blue Dolphin DVD release.

- The humour of this concept becomes even broader in Hooper’s sequel. Finally coming face-to-face with Dennis Hopper’s evangelist and chainsaw-wielding Texas Ranger, who announces that he is ‘the Lord of the Harvest,’ the cook immediately assumes that this must be a business rival. ‘Who’s that?’ he asks, ‘some new health-food restaurant?’

WORKS CITED

Balun, Chas. (1986). Horror Holocaust. New York: Fantaco.

Benton, Mike. (1991). The Illustrated History of Horror Comics. Dallas: Taylor.

Bloch, Robert. (1962). Psycho London: Corgi.

Brottman Mikita. ‘Stories of Childhood and Chainsaws.’ Cinefantastique 27. February 6, 1996.

Capote, Truman. (1966). In Cold Blood: A True Account of a Multiple Murder and Its Consequences. London: Hamish Hamilton.

Clover, Carol J. (1992). Men, Women and Chainsaws: Gender in the Modern Horror Film. London: BFI.

Collis, Clark. ‘Unhappy, Texas.’ Empire 133. July 2000.

Ellis, Bret Easton. (1991). American Psycho. London: Picador.

Fallen, John. Review of The Texas Chainsaw Massacre Part 2. Arrow in the Head. Available at: http://www.joblo.com/arrow/texaschainsaw2.htm (Accessed August 30, 2017).

Fielder, Leslie A. (1984). Love and Death in the American Novel. London: Penguin.

Gagne, Paul R. (1987). The Zombies that ate Pittsburgh: The Films of George A. Romero. New York: Dodd, Mead & Co.

Imhoff, David and Collins, Nancy A. (writers), Butler, Jeff (illustrator). Jason versus Leatherface. 3 issues. Topps Comics. October 1995 – January 1996.

Jaworzyn, Stefan. (2003). The Texas Chainsaw Massacre Companion. London: Titan.

Kermode, Mark. (1999). ‘Texas Chainsaw Massacre 2.’ Time Out Film Guide 7th ed. London: Penguin.

King, Stephen. (1982). Danse Macabre. London: Futura.

Wood, Robin. (1978). ‘Return of the Repressed.’ Film Comment. July/August.

Woods, Paul Anthony. (1995). Ed Gein: Psycho. New York: St Martin’s Press.

[…] To continue reading please click here […]

[…] The Saw Is Family (The Texas Chainsaw Massacre) […]