Before Elvis, there were EC comics.

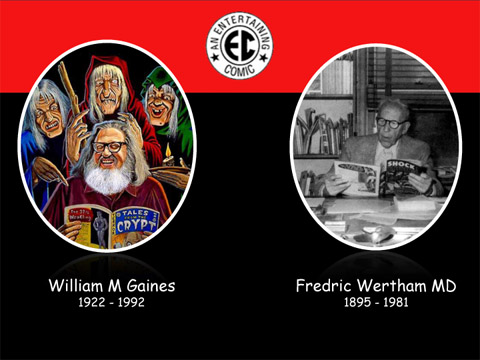

In 1944, American publisher Max Gaines established ‘Educational Comics,’ with a view to selling ‘Picture Stories’ from the Bible, history and science to schools and churches. The pulp magazines that had inspired comics were merging with paperback novels and passing away, and this separation of popular literature from sequentially illustrated stories drew a cultural line between popular fiction aimed at adults (which was text-based), and children (which was graphic). Gaines died saving a child in a boating accident in 1947, leaving EC to his son, ‘Bill.’

Bill Gaines re-branded as ‘Entertaining Comics,’ leading with new crime titles heavily influenced by pulp detective fiction and film noir. Gaines’ other inspiration was radio, in particular Inner Sanctum Mysteries and The Witch’s Tale – horror anthologies introduced by camp hosts that combined Gothic framing devices with a gallows humour. In 1949, Gaines added ‘illustrated stories’ from ‘the Vault of Horror’ and ‘the Crypt of Terror’ to War Against Crime! and Crime Patrol. Short sharp shockers were introduced by the ‘Vault Keeper’ and the ‘Crypt Keeper.’ A year on, Gaines launched a ‘New Trend’ led by Tales from the Crypt, The Vault of Horror, The Haunt of Fear, Weird Science, Weird Fantasy and Crime Suspense Stories. The target audience were young men, although kids could and did buy them.

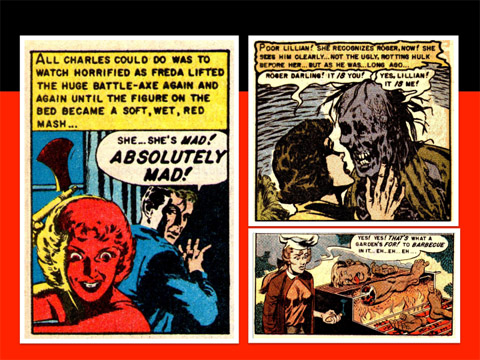

Johnny Craig drew the Vault Keeper, and his apprenticeship on EC crime comics had produced a visual style as clean as a Madison Avenue advertisement. Craig’s contemporary realism served to make the insane violence apparently simmering in suburbia all the more disturbing. Jack Davis exploited the gothic otherness of his native South, filling it with atavistic cannibals and psychos. A ‘typical Jack Davis story,’ wrote Mike Benton, ‘takes place in a backwater village, populated by [incestuous] cretins … and evil – degenerate, perverse evil – pulses, throbs, and swells on every page’ (Benton 14 – 15).

Point of view was often second person, making the narrative intimate, sensual and disturbing. The first act followed crime codes, while the third was a Gothic epiphany. Plots had a contemporary setting, and frequently focused on co-dependant family or business relationships. Characters (including children) were either predators or prey, and the solution was always murder – the victim invariably returning from the grave to exact a terrible, and smelly, revenge. The horror hosts shared a ghoulish delight in describing decay – like their ubiquitous zombies, these were stories you could smell.

In a Writer’s Digest ‘Help Wanted’ column, Gaines summarised his formula: ‘We have no ghosts … We tolerate vampires and werewolves …. We love walking corpse stories … and we relish tales of sadism. Virtue doesn’t always have to triumph’ (qtd. in Benton 23). EC had updated the traditional Gothic, fused it with pulp/noir, and dropped it into the heart of the post-war American Dream.

Vengeful revenants featured heavily, and these unexplained, preternatural denouements can be read in the context of the literary Gothic, as, in Victor Sage’s terms, ‘transgressive’ moments’ – the instant of cultural and epistemological displacement in which: ‘an older universe of “superstition” and barbarity rushes momentarily into the vacuum left by civilized, “modern,” reasonable doubt’ (Sage 4). There were Christmas stories with coffins under the tree; zombie-lovers embraced with maggoty smooches; insensitive husbands were barbecued; kids framed their parents for murder; gamblers bet body parts; and baseball diamonds were marked out with human intestines. Disney was inverted in ‘Grim Fairy Tales.’

The sincerest form of flattery followed. By 1954 here were over a hundred competing horror titles in the market. Gaines was unconcerned: ‘We figured we could out-gross everyone, and we did!’ (qtd. in Mann, 1990).

Comics had been studied by educational psychologists since the twenties. Research usually focused on literacy, and was not widely read outside academic journals. In 1927, for example, Lehman and Witty argued that reading comics was a Cathartic ‘play activity’ (Lehman and Witty: 1927, 211), although Witty later advised teachers that the ‘problem’ of comics could be countered by the ‘antidote’ of ‘good books’ – he recommended Disney Readers (Witty: 1941, 104).

Josette Frank of the Child Study Association of America researched comics as a genre of children’s literature throughout the forties. Frank retained Witty’s division between literature and popular culture, but believed that comics could be a springboard towards more sophisticated reading. She concluded that comics were not harmful, arguing that: ‘A child who is already disturbed by some emotional conflict may be upset by reading either comics or classics’ (Frank, 1943, 162).

Frank was responding to a Chicago Daily News article, in which the children’s author Sterling North denounced comic book publishers as ‘guilty of a cultural slaughter of the innocents.’ North claimed that comics were a ‘hypodermic injection of sex and murder,’ sensationally concluding that: ‘Unless we want a coming generation even more ferocious than the present one, parents and teachers throughout America must band together to break the “comic” magazine’ (qtd. in Krensky 27).

It was North’s alarmist application of the Behaviourist ‘hypodermic syringe model of communication’ that set the tone, establishing a bourgeois myth in which comics were implicitly harmful, and from which children required protection by parents, teachers, and Walt Disney, lest parents required protection from them. This argument was given scientific credibility by the psychiatrist Fredric Wertham, who began publishing on the relationship between comics and juvenile delinquency in 1948.

Publishers responded by forming the Association of Comics Magazine Publishers, and establishing a self-regulating code of practice. The ‘Star’ stamp of approval approved pretty much anything however, and the scheme collapsed when EC and Avon withdrew.

In 1950, Democratic Senator Estes Kefauver, Chair of the Senate’s Special Committee to Investigate Organised Crime, established a subcommittee to investigate Wertham’s theories, but it was found that during the period in which comics increased in popularity (1945 – 1950), juvenile crime had actually declined (Springhall, 131). Undeterred, Wertham convinced the New York State Joint Legislative Committee to investigate comics, and, in 1952, the State Assembly passed a bill making it a misdemeanour to ‘publish or sell comic books … that might incite minors to violence or immorality’ (qtd. in Benton, 41). Republican Governor Thomas E. Dewey, however, vetoed the bill as ‘unconstitutional.’

Wertham continued to lobby, publishing The Seduction of the Innocent: The Influence of Comic Books on Today’s Youth in 1954: ‘Up to the beginning of the comic-book era,’ he wrote, ‘there were hardly any serious crimes such as murder by children under twelve’ (Wertham, 155).

Wertham resembled North in rhetorical style, and terrifying case studies assaulted the reader on every page: ‘Three boys, six to eight years old, took a boy of seven, hanged him nude from a tree, his hands tied behind him, then burned him with matches. Probation officers investigating found that they were re-enacting a comic book plot’ (Wertham, 150). The Freudian frame was persuasive, and Fritz Lang endorsed Wertham by showing the baby-faced, ‘lipstick killer’ reading horror comics in While the City Sleeps. The Chicago School, however, criticised Wertham’s lack of statistical evidence, while Commentary’s Robert Warshow noted that although he didn’t approve of his son’s comics, he couldn’t see them having ‘any very specific effects.’ He also admitted that EC’s Mad Magazine was ‘pretty good’ (Warshow, 1954).

Wertham’s sample was imprecisely documented, and there was no ‘control group.’ His evidence was anecdotal, he quoted out of context, there were no references, and no bibliography. Given the text’s dissemination through popular magazines, it is likely that Wertham was preaching to a general audience.

Roger Sabin called Wertham’s book his ‘Mein Kampf ’ (Sabin, 158), which was clever but inappropriate. Wertham was a German Jew, and his horror of fascism was a controlling metaphor – he repeatedly compared Superman to Hitler, asking: ‘How did Nietzsche get into the nursery?’ (Wertham, 15). Wertham spoke from experience when he paraphrased Irwin Edman: ‘It does not take long for a society to become brutalized’ (Wertham, 395).

Corroborating, to a certain extent, his thesis, a media-driven moral panic followed. Church groups and PTAs organised public comic book burnings. The Senate Subcommittee to Investigate Juvenile Delinquency was reconvened, and Wertham and his arch nemesis, Gaines, appeared on the same day.

Testimony was filmed and broadcast. Wertham was used to public speaking, while Gaines, however, did not look good on television. He was oratorically out of his depth, and rattled by an accusation of racism from Wertham. (EC’s agenda was quite clearly liberal.) Gaines spoke as an educated, creative practitioner in a free market; citing Judge Woolsey’s repeal of the Ulysses ban, and explaining genre, narrative and graphic devices to Ivy League politicians that despised popular culture, and the subversive anti-realism of both Modernism and the Gothic.

The subcommittee was not ‘McCarthyist,’ neither were members convinced by Wertham. The cross-examination was, instead, based around the concept of ‘taste,’ a term recklessly introduced by Gaines. Senator Kefauver then asked him to explain a Johnny Craig cover illustration in this context: ‘This seems to be a man with a bloody axe holding a woman’s head up which has been severed from her body. Do you think that is in good taste?’ Gaines replied that he did, ‘for the cover of a horror comic’ (qtd. in Springhall, 138 – 139).

Gaines was fighting on two flanks. Wertham’s ‘effects theory’ reflected a common bourgeois fear of working class youth, framed by an essentially Christian appeal for the moral protection of ‘innocence’ – the presumed pre-lapsarian state of children reflecting a wider cultural desire for Grace, a fear of corruption, and the familiar scapegoating of new media and popular narratives. The Seduction of the Innocent therefore deployed the same implicit causal arguments as, for example, the New York Society for the Suppression of Vice.

In addition to Wertham’s monocausal thesis, Gaines was also debating Kefauver on the nature of cultural value. Kefauver’s interpretation of ‘good’ and ‘bad’ taste, therefore, indicated a hierarchical discrimination in which Gaines’ medium was rejected as juvenile (rather than adult and literary), and aesthetically illegitimate. John Springhall reads the ‘taste’ argument as ‘a symbolic weapon in the struggle for ideological domination, between established cultural arbiters and a new generation of commercial harbingers’ (Springhall, 139).

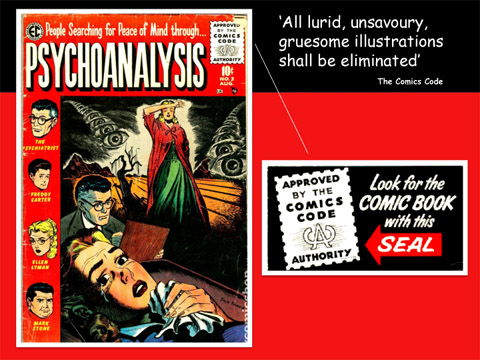

The subcommittee’s interim report rejected Wertham’s model. (Wertham went on to campaign against violence on television.) Nonetheless, it concluded that ‘this nation cannot afford the calculated risk involved in the continuing mass dissemination of crime and horror comics to its children’ (qtd. in Springhall, 139). Censorship would have been a violation of the First Amendment, but the message was clear. The industry chose self-regulation. The Comics Magazine Association of America was founded in 1954, with editorial standards to be monitored by the independent Comics Code Authority, under Judge Charles Murphy. ‘General Standards’ included:

Respected institutions shall never be presented in such a way as to create disrespect for established authority.

Romance stories shall emphasise the value of the home and the sanctity of marriage.

All scenes of horror, excessive bloodshed, gory or gruesome crimes, depravity, lust, sadism, [and] masochism shall not be permitted.

Scenes dealing with … walking dead, torture, vampires … ghouls, cannibalism, and werewolfism are prohibited.

In every instance good shall triumph over evil.

The injunctions that: ‘Restraint in the use of the word “crime” in titles … shall be exercised,’ and, ‘No comic magazine shall use the word horror or terror in its title’ killed off the majority of the EC lines. Gaines attempted a ‘New Direction,’ but wholesalers and retailers refused to handle EC titles, with the exception of Mad Magazine, which was Code exempt, and fittingly prospered as a satire of American culture, which was exactly what the horror comics had always been.

The final EC comic was Incredible Science Fiction 33, which included a civil rights allegory about a black astronaut entitled ‘Judgement Day.’ Murphy initially rejected the story because of the beads of sweat on the astronaut’s brow.

Although mainstream American comics were now effectively G-rated by a rigorously conservative manifesto, the transgressive graphic and narrative sophistication of EC was a clear intertextual influence on the next generation. For the counter-cultural and revolutionary ‘underground’ comics of the 1960s, EC was emblematic of the artistic struggle against censorship and hegemony. Ron Turner, for example, re-created Weird Science covers for his Slow Death ‘True War Tales,’ protesting Vietnam and South African apartheid.

A new generation of independent film-makers were also pursuing horror as cultural critique, while abandoning the Gothic revivals of Hammer and American International. George A. Romero’s savage satire on segregation and consumerism, Night of the Living Dead (1968), ignores the traditional, post-colonial ‘zombie’ archetype in favour of the EC model. ‘The ECs influenced me greatly,’ Romero has admitted, continuing:

I think a great part of my aesthetics in the genre was born out of EC rather than movies. Horror movies, when I was in my formative years, were generally bad … The ECs on the other hand, were … gritty, there was a lot going on in each frame, the stories were great, and the effects were sensational! (qtd. in Gagne, 126).

Romero also crossed the Johnny Craig story ‘Frozen Assets’ with an adaptation of Poe’s ‘Facts in the Case of M. Valdemar’ in Two Evil Eyes (1990), and collaborated with Stephen King on the EC-inspired anthology Creepshow (1982). Replicating an EC comic on screen was not a new idea. Amicus Productions made a series of EC inspired movies between 1964 and 1973, including the direct adaptations Tales from The Crypt (1972), and The Vault of Horror (1973). (Ralph Richardson played the Crypt Keeper.) Robert Bloch wrote the anthology Asylum for Amicus in 1972, and his novel of 1960, Psycho (and Hitchcock’s seismic adaptation), with its crime-to-Gothic plot, slightly seedy protagonists, and motel hell scenario, is clearly in the EC mode.

Stephen King has also acknowledged his debt to EC, writing that: ‘As a kid, I cut my teeth on William Gaines horror comics.’ For King, EC comics ‘sum up … the epitome of horror, that emotion of fear … [that] also invites a physical reaction by showing us something which is physically wrong’ (King, 36). In his analysis of American Gothic, Danse Macabre (1982), King cites Gaines alongside Poe in terms of cultural significance.

King also used the EC device of placing Gothic archetypes in a contemporary setting – his second novel Salem’s Lot (1975) achieving with vampires what Hammer had failed to do in Dracula: A.D. 1972 (1972). Salem’s Lot was directed for television by Tobe Hooper in 1979, depicting vampires more like EC zombies than the prevailing Romantic stereotype.

Hooper is the quintessential heir to the EC aesthetic, in particular the work of Jack Davis. ‘I started reading [EC comics] when I was about seven,’ he told Cinefantastique in 1977, ‘I loved them … Since I started reading these comics when I was young and impressionable, their overall feeling stayed with me. I’d say they were the single most important influence on The Texas Chainsaw Massacre’ (qtd. in Jaworzyn, 30). In concept, character and controversy, Hooper’s meat movie masterpiece was pure EC, and his next movie, Death Trap (AKA Eaten Alive, 1976), was based on a Haunt of Fear story by Jack Davis called ‘Country Clubbing.’ Hooper lit from a comic book palette, while his vérité style recalled the intimate perspective of EC narratives, as did his relentless parodies of the American family. There was also a common preoccupation with cannibalism, necrophilia and putrefaction. In Poltergeist (1982), Hooper blended the Twilight Zone story ‘Little Girl Lost’ with the Vault of Horror story ‘Graft in Concrete’ (again by Jack Davis).

In rock ‘n’ roll, meanwhile, the EC influence can also be seen in Alice Cooper, The Cramps, Michael Jackson’s Thriller and, more recently, in the films of the alternative metal-head, Rob Zombie.

Rob Zombie’s hyper-real homage to Hooper and EC, House of 1000 Corpses (2003), is framed by a scary clown who addresses the viewer directly from the diegetic world of the narrative: ‘Howdy Folks! Do you like blood, violence, freaks of nature? Then come on down to Captain Spaulding’s Museum of Monsters and Madmen…’ (The humour is encoded in the reference to Groucho Marx.) Not getting the joke, Universal delayed release for almost four years, and Zombie, along with Eli Roth, the writer/director of Hostel, had his work labelled ‘Torture Porn’ by David Edelstein, the chief film critic of New York Magazine.

A textual doubling has now occurred in American Gothic, in which genre artefacts are critically and aesthetically labelled as either legitimate or illegitimate. Time is a factor, as both EC comics and The Texas Chainsaw Massacre are now artistically valid and academically respectable.

Other divisions remain ideological. ‘Police Procedurals’ are now a staple of prime-time TV, with Bones and the CSI franchise routinely depicting decomposition with an EC-like verisimilitude that would have been unacceptable to the FCC, the MPAA and, indeed, the Comics Code a decade ago. Good taste would appear to be guaranteed by major network distribution and a positive portrayal of law enforcement.

The extreme violence and lack of moral centre in the work of directors like Zombie remains more difficult to accept. Kira Cochrane reads so-called ‘Torture Porn’ as violently misogynist (Cochrane 2007), while Edelstein likens the audience to self-harmers (Edelstein 2006). Curt Purcell laments the loss of subtle horror (2011), while Steve Biodrowski dismisses the films as: an ‘escapist sideshow that pretends to confront its audience with “realistic” horror while actually dodging reality’ (Biodrowski 2008). Kim Paffenroth compares with the aesthetically justifiable violence of Sophocles and Shakespeare (Paffenroth 2011), while Psychologist Dave Grossman – in Stop Teaching Our Kids to Kill – argues that violence in television, movies and video games contributes to real-life violence by a process of training and desensitisation similar to combat experience (Grossman 1999).

With ‘Torture Porn’ we come full circle. Imagery and rhetoric recycles from the days of Tales From The Crypt and The Seduction of the Innocent. The influence of Gaines and Wertham would seem to have no end.

WORKS CITED

Barker, Martin. (1984). A Haunt of Fears: The Strange History of the British Horror Comics Campaign. London: Pluto.

Benton, Mike. (1991). The Illustrated History of Horror Comics. Dallas: Taylor Publishing.

Biodrowski, Steve. (2008). ‘Cybersearching: Torture Porn Debate. Available from: http://cinefantastiqueonline.com/2008/05/cybersurfing-torture-porn-debate/ (Accessed April 09 2011).

Cochrane, Kira. ‘For your entertainment.’ The Guardian. May 1, 2007, pp. 4 – 7.

Edelstein, David. (2006). ‘Now Playing at Your Local Multiplex: Torture Porn.’ The New York Magazine. Available from: http://nymag.com/movies/features/15622/ (Accessed April 09 2011).

Frank, J. (1942). ‘Let’s Look at the Comics.’ Child Study, 19(3), 76-77, 90-91.

—. (1943). ‘The role of comic strips and comic books in child life.’ Supplementary Educational Monographs, 57, 158-162.

—. (1944). ‘What’s in the Comics?’ Journal of Educational Sociology, 18(4), 214-222.

—. (1949). ‘Some Questions and Answers for Teachers and Parents.’ Journal of Educational Sociology, 23(4), 206-214.

Gagne, Paul R. (1987). The Zombies that Ate Pittsburgh: The Films of George A. Romero. New York: Dodd, Mead & Co.

Grossman, David. (1999). Stop Teaching Our Kids to Kill: A Call to Action against TV, Movie and Video Game Violence. New York: Crown.

Jaworzyn, Stefan. (2003). The Texas Chainsaw Massacre Companion. London: Titan.

King, Stephen. (1982). Danse Macabre. London: Futura.

Krensky, Stephen. (2008). Comic Book Century: The History of American Comic Books. Minneapolis: Twenty-First Century Books.

Lehman, H.C. and Witty, P.A. (1927). ‘The compensatory function of the Sunday “funny paper.”’ Journal of Applied Psychology 11(3) 202 – 211.

Paffenroth, Kim. (2011). ‘Gospel of the Living Dead.’ Available from: http://gotld.blogspot.com/ (Accessed April 09 2011).

Purcell, Curt. (2011). ‘The Groovy Age of Horror.’ Available from: http://groovyageofhorror.blogspot.com/ (Accessed April 09 2011).

Sabin, Roger. (1993). Adult Comics. London: Routledge.

Sage, Victor. (2004). Le Fanu’s Gothic: The Rhetoric of Darkness. London: Palgrave Macmillan.

Springhall, John. (1998). Youth, Popular Culture and Moral Panics. London: MacMillan.

Warshow, Robert S. (1954). ‘The Study of Man: Paul, the Horror Comics, and Dr. Wertham.’ Commentary. Available from: http://www.commentarymagazine.com/article/the-study-of-man-paul-the-horror-comics-and-dr-wertham/ (Accessed April 10 2011).

Wertham, Fredric. (1955). Seduction of the Innocent. London: Museum Press.

Witty, P.A. (1941). ‘Children’s Interest in the Comics.’ Journal of Experimental Education, 10(2), 100-104.

Witty, P.A. (1941). ‘Reading the Comics—A Comparative Study.’ Journal of Experimental Education, 10(2), 105-109.

Previously unpublished, paper originally presented at the Watching the Media; Censorship, Limits, and Control in Creative Practice Symposium, Edge Hill University, Liverpool, April, 2011

Copyright © SJ Carver 2011, 2013

[…] Weird Tales from the Vault of Fear: The EC Comics Controversy and its Legacy […]

[…] Weird Tales from the Vault of Fear: The EC Comics Contr… […]