During the fourth book of Ainsworth’s gothic novel Rookwood (1834), in a chapter entitled ‘The Phantom Steed,’ the highwayman Dick Turpin becomes aware of a ghostly horseman riding by his side in the midnight mist during his fabled ride to York. Book IV is in fact called ‘The Ride to York,’ and is the dramatic focal point of Rookwood while paradoxically having nothing whatsoever to do with the primary plot. Eventually the apparition resolves itself into the figure of the novel’s romantic anti-hero, Luke Rookwood. They ride together for a while, and then Luke vanishes into the night to resume his by then near-demented pursuit of the novel’s gothic heroine and final girl, Eleanor Mowbray. The next time the two men meet, Turpin absent-mindedly gives Luke a package he has been holding for the gypsy sorceress Barbara Lovel. It contains a poisoned lock of Luke’s dead lover Sybil’s hair, which he kisses and then promptly dies. This pair of connected events very much symbolises the structure of Rookwood, which is in fact two texts riding together in parallel before Text B, The Ride to York (starring Dick Turpin), completely overwhelms Text A, Rookwood, A Romance (a gothic melodrama about the rivalry of the half-brothers Luke and Ranulph Rookwood). The Ride to York was frequently published and performed in the penny gaffs separately, completely divorced from Rookwood.

The Turpin narrative does however intersect with the gothic melodrama of Rookwood on occasion. As Ainsworth’s Turpin is a simple prototype for the later characterisation of Jack Sheppard, so the connection between the gothic narrative and representations of the criminal underworld is beginning to be explored. Turpin, the glorious social outsider, often appears outside nature as well: ‘Talking of Dick Turpin, they say, is like speaking of the Devil,’ says the sexton, Peter Bradley (Sir Piers Rookwood’s long-lost and disgraced brother, Alan, in disguise), ‘he’s at your elbow ere the word’s well out of your mouth’ (Ainsworth 58). Turpin is twice taken for an apparition by other characters; once when he disguises himself intentionally as the ghost of Sir Piers in order to rob the house, and later as himself, or at least the self wearing the mask of the highwayman. Here he is mistaken for the devil incarnate in a characteristically Ainsworthian gothic gesture:

‘Stay’, cried the sexton. ‘He is not in pursuit – he takes another course – he wheels to the right. By Heaven! it is the Fiend himself upon a black horse, come for Bowlegged Ben. See, he is there already’ (Ainsworth 133).

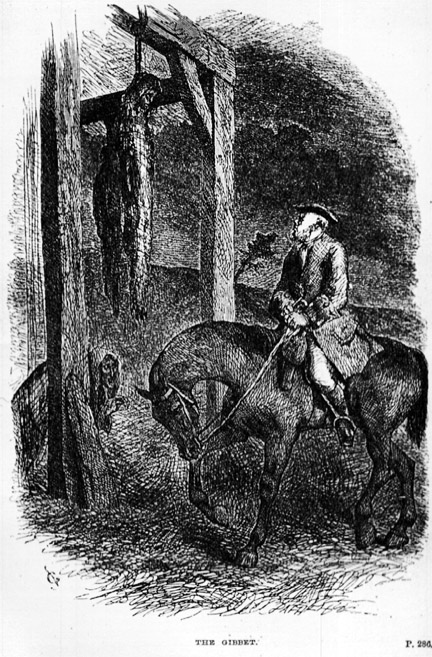

The horseman had turned, as the sexton stated, careering towards a revolting object at some little distance on the right hand. It was a gibbet, with its grizzly burden. He rode swiftly towards it, and, reigning in his horse, took off his hat, bowing profoundly to the carcass that swung in the morning breeze.

But, before diffusing the image by identifying Turpin, an ambivalent supernatural event occurs, and the author’s natural explanation occupies the same space as the sexton’s superstitious allusion to an ominous crow, while also mischievously punning on ‘blade’ to signify the likelihood of the dissection knife as Turpin’s ultimate post mortem punishment after his inevitable execution:

Just at that moment a gust of air catching the fleshless skeleton, its arms seemed to be waved in reply to the salutation. A solitary crow winged its flight over the horseman’s head as he paused. After a moment’s halt he wheeled about, and again shouted to Luke, waving his hat.

‘As I live’, said the latter, ‘it is Jack Palmer.’

‘Dick Turpin, you mean’, rejoined the sexton. ‘he has been paying his respects to a brother blade. Ha, ha! Dick will never have the honour of a gibbet; he is too tender of the knife. Did you mark the crow? But here he comes.’ And in another instant Turpin was by their side (Ainsworth 133).

Turpin is, in effect, already larger than life; even his human identity seems called into question. Already it is apparent that, in his case at any rate, death is not the end.

Although originally intended as a secondary character, the ghost of Dick Turpin had seized the imagination of the author to the extent that:

The Ride to York was completed in one day and one night … Well do I remember the fever into which I was thrown during the time of composition. My pen literally scoured over the pages. So thoroughly did I identify myself with the flying highwayman, that, once started, I found it impossible to halt. Animated by kindred enthusiasm, I cleared every obstacle in my path with as much facility as Turpin disposed of the impediments that beset his flight. In his company, I mounted the hill-side, dashed through the bustling village, swept over the desolate heath, threaded the silent street, plunged into the eddying stream, and kept an onward course, without pause, without hindrance, without fatigue. With him I shouted, sang, laughed, exulted, wept. Nor did I retire to rest till, in imagination, I heard the bell of York Minster toll forth the knell of poor Black Bess (Ainsworth, preface to Rookwood) (1).

Ainsworth’s passion for his subject is still apparent 14 years on, in the richness of the language he uses to recall what must have been his finest hour: on the brink of fame and fortune, darling of the D’Orsay set, and before the collapse of his marriage, the death of his wife and a long legal battle with his in-laws over the custody of his children and the vicious critical attacks of the Newgate controversy. Although we might now regard the publication of Rookwood as, in fact, a contributory factor in his later denigration, there is a combination of conviction and innocence in the author’s heart that rejects such an interpretation. Ainsworth’s initial enthusiasm had been infectious, and an eighteenth century, chapbook fascination with outlaws that had lain dormant since the days of Defoe became a national craze once more; a fashion that even crossed the boundaries of social class for a time. As Charles Mackay complained in 1841:

Turpin’s fame is unknown to no portion of the male population of England after they have attained the age of ten. His wondrous ride from London to York has endeared him to the imagination of millions; his cruelty in placing an old woman upon a fire, to force her to tell him where she had hidden her money, is regarded as a good joke; and his proud bearing upon the scaffold is looked upon as a virtuous action (Mackay 634).

There are so many contemporary accounts of the incident with the fire that it is probably true, the ride to York is purely an invention of Ainsworth’s. S.M. Ellis wryly observed that Rookwood ‘may be styled another “novel without a hero”’ (Ellis I.239), while George J. Worth favoured Luke Rookwood as ‘the tortured protagonist’ (Worth 94). The brooding, fated Luke is in fact curiously situated dramatically somewhere between the roles of romantic hero and the gothic villain (which were always both sides of the same coin), while the much more vanilla-flavoured Ranulph Rookwood is the generic melodramatic hero. Dick Turpin, on the other hand, was, as author and audience understood all along, ‘an English Adventurer’ (Ainsworth 47).

‘Turpin was the hero of my boyhood,’ the author later admitted in his preface to the 1849 edition of Rookwood:

I had always a strange passion for highwaymen, and have listened by the hour to their exploits, as narrated by my father, and especially to those of ‘Dauntless Dick’, that ‘chief minion of the moon’ (2). One of Turpin’s adventures in particular, the ride to Hough Green, which took deep hold of my fancy, I have recorded in song. When a boy, I have often lingered by the side of the deep old road where this robbery was committed, to cast wistful glances into its mysterious windings; and when night deepened the shadows of the trees, have urged my horse on his journey, from a vague apprehension of a visit from the ghostly highwayman. And then there was the Bollin, with its shelvy banks, which Turpin cleared at a bound; the broad meadows over which he winged his flight; the pleasant bowling-green of the pleasant old inn at Hough, where he produced his watch to the Cheshire squires, with whom he was upon terms of intimacy; all brought something of the gallant robber to mind. No wonder, in after years, in selecting a highwayman for a character in a tale, I should choose my old favourite, Dick Turpin (Ainsworth, preface to Rookwood).

This was written after the Newgate Controversy had permanently undermined his literary reputation, but Ainsworth refuses to go with the flow and preach about the moral dangers of rendering outlaws heroic in works of fiction. Note the romantic fascination of the language, which is at times almost reverential as befitting a description of such superhuman feats as the non-stop ride to Hough Green (which becomes the Ride to York in Rookwood and popular history). This honest confession of childhood fancy also demonstrates the coexistence of the oppositional emotional responses to crime and violence that he was able to tap into as an adult author. The avenue of trees gives the young rider the creeps, but his glances are ‘wistful’ ones for an age now past; having not been blessed with a vision, Ainsworth had to resurrect Turpin himself.

The commercial success of Rookwood had much to do with this appeal to the imagined freedom of an earlier age. With this creation, or recreation, of the famous Georgian outlaw, Ainsworth was the catalyst for a whole new style of picaresque narrative. Although his contribution to the Newgate genre of the nineteenth century was not the first (Lytton had published Paul Clifford in 1830) (3), it was, and is, Ainsworth’s romantic version of the outlaw that endures in the popular imagination (first in England and then, particularly, America in the figure of the Western frontier outlaw), rather than Lytton’s erudite radical, Paul Clifford, or all the inhabitants of Dickens’s Victorian underworld, except when, like the Artful Dodger, they were read as if written by Ainsworth. In the second edition of his Memoirs of Extraordinary Popular Delusions and the Madness of Crowds (1852), for example, Charles Mackay quoted several interviews with young offenders taken from the Sixth Report of the Inspector of Prisons for the Northern Districts of England in which the Artful Dodger was viewed as a ‘Jack Sheppard’ figure, Jack Sheppard being Ainsworth’s next rehabilitated and romanticised eighteenth century criminal after Dick Turpin, from the 1839 novel of the same name (Carver 226).

Writing, for example, of the robbery of the Union Pacific Railroad Company by Butch Cassidy and the ‘Wild Bunch’ in 1900, Fenin and Everson argue that: ‘Such exploits vividly aroused popular fantasy, and the traditional sympathy of the American masses for the underdog, fanned by sensational newspaper reports, provided ideal ground for the emergence of the myth of the outlaw. They provided ground, too, for the physical expression of those stark puritanical values implicit in the struggle between good and evil, which have so affected the American unconscious as revealed in the country’s folkways and mores’ (Fenin and Everson 9). There was also cultural cross fertilisation between English fictionalised outlaws and their real equivalents in the old west: the famous letters sent to the Kansas City Star by Frank and Jesse James were signed ‘Jack Sheppard’ (Bloom 86). Stories from the frontier as well as James Fenimore Cooper’s importation and application of the codes of English historical romance (both in the manner of Scott and James and, in the later Leatherstocking Tales, Lytton and Ainsworth) to the new values of the New Republic created an enduring image of rough justice and outlaw nobility that could have no place in Victorian England, as evident during the ‘Newgate Controversy’ of 1839, a moral panic that left Ainsworth’s serious literary reputation in tatters after the publication of Jack Sheppard. Notably however, Ainsworth’s literary reputation remains intact in the United States.

There were of course many versions of the life and legend of Dick Turpin already in place in English culture by the time of Rookwood, ranging from the official record of his pursuit, accidental capture, and trial and execution in York in 1839, to chapbook romances, Newgate Calendars, Defoe’s Newgate biographies, The Beggar’s Opera and a positive legion of folk songs and tall stories among the lower classes. If a fraction of the contemporary reports of Turpin’s criminal behaviour is true (particularly during his time with the ‘Gregory Gang’ in North London in the early 1830s, from which we get the story of the old lady and the fire), then the original was undoubtedly a murderous, self-serving, sadistic, petty and quite mediocre little man. As Hilary and Mary Evans begin their exploration of the cult of the highwayman (of which Dick Turpin must be the quintessential symbol in English folklore):

They robbed and raped and murdered. They lied and cheated, betrayed and deceived. When it served their purpose, they stole a man’s property, used his wife or his daughter, destroyed his home and livelihood, took his life. When they gave, it was only a bribe; when they showed consideration, it was to buy goodwill. If they claimed to have been unjustly treated by society, it was to justify themselves for flouting society’s rules; when they claimed to be revenging themselves on society for its injustice, they took their revenge on the weak and innocent more often than on those who had caused the injustice (Evans and Evans 1).

Turpin being one of the worst offenders, yet these men, along with the outlaws of the American Frontier, even in their own day, were more often than not portrayed as heroic, if not downright chivalrous. In a ballad popular around the time of his execution entitled ‘Turpin’s Appeal to the Judge,’ Turpin was already being portrayed as a Robin Hood figure (another enduring fiction):

I hope, my Lord, you’ll pardon me,

I’m not the worst of men.

I the Scripture have fulfilled

Though a wicked life I’ve led,

When the naked I beheld,

I’ve clothed them and fed.

Sometimes in a coat of winter’s pride,

Sometimes in a russet grey,

The naked I’ve clothed, the hungry fed,

And the rich I’ve sent away (qtd. in Linebaugh 203-204).

So strong was this perception of the heroic ‘gentleman of the road’ that the tagline of the LWT series Dick Turpin was: ‘Dick Turpin is a brilliant rider and master swordsman whose belief in liberty and his own rough justice make him an outlaw in the perilous and corrupt world of eighteenth century England’ (Carpenter 1979). The show aired in 1979, 240 years after the death of the original. Richard O’Sullivan played the title role à la Robin Hood; there was even a Sheriff of Nottingham figure called Captain Spiker.

Proving that what goes around comes around, 1979 was also the zenith of the punk rock era in Great Britain, and The Sex Pistols had already looked towards eighteenth century pirates, smugglers and even the Gordon Rioters as the ancestors of working class Punk sensibility during (manager) Malcolm McLaren’s masterful campaign of media exploitation. Dick Turpin was obviously ripe for remarketing and the TV series was a great success; similarly, who could forget ‘Stand and Deliver’ (1981) by Adam and the Ants? The character has also been played on the big screen by Golden Age Hollywood cowboy stars Matheson Lang in 1922, Tom Mix in 1925 and Victor McLaglen in 1933; the fictionalised English Highwayman translating easily to the hyper-real western outlaw figure. Turpin was also played by Louis Hayward in 1951, David Weston (for Disney) in 1965, and Sid James (Carry On Dick) in 1974. More recently, Johnny Depp’s Captain Jack Sparrow from the ongoing film series Pirates of the Caribbean directed by Gore Verbinski is also just Dick Turpin on a boat instead of a horse. Jake Scott’s underrated British film Plunkett and Macleane (1999) is an interesting return to the Newgate Calendars, combining the bawdy humour of Carry on Dick with Butch Cassidy and the Sundance Kid, and obviously taking as its inspiration from the real life partnership of Dick Turpin and Tom King. Sources from the anonymous authors of Newgate Calendars to cultural historians such as Hilary and Mary Evans agree that this business arrangement, begun when Turpin attempted to rob fellow highwayman King, was terminated when he accidentally shot his partner in crime during an argument over a stolen horse with the landlord of the Green Man inn, Epping. (King survived for a week and sang like a canary.) Legend has it that Turpin vowed vengeance against the landlord, but he never made good his threat. Interestingly, Ainsworth makes this event a matter of prophecy in Rookwood: ‘”I shall never come to the scragging post, unless you turn topsman, Dick Turpin,”’ says King, ‘”My nativity has been cast, and the stars have declared I am to die by the hand of my best friend – and that’s you – eh, Dick?”’ (Ainsworth, Rookwood, 255).

The moral reversal inherent in the Robin Hood rhetoric surrounding Turpin is a common feature in outlaw narrative. In a corrupt social system the outlaw must be the honest man, the rebel, the freedom fighter and, by definition, the hero. Although such figures are not necessarily without historical precedent, such as Sandor Rozsa, the ‘bandit of the plains,’ a Hungarian brigand who became a national guerrilla leader in the 1848 Kossuth rebellion, or Pancho Villa, the Mexican bandit turned revolutionary general in the early years of his country’s long revolution (1910-40), they are very, very rare. So why should such myths persist?

Eric Hobsbawm pursues a possible answer in the concept he designates as ‘social banditry’:

The point about social bandits is that they are peasant outlaws whom the lord and the state regard as criminals, but who remain within peasant society, and are considered by their people as heroes, as champions, avengers, fighters for justice, perhaps even leaders of liberation, and in any case men to be admired, helped and supported (Hobsbawm 13).

‘Banditry is freedom,’ says Hobsbawm, ‘but in peasant society few can be free’ (Hobsbawm 24). We might also pause to consider the difference between the public perception of this type of outlaw, invariably deemed heroic, as opposed to other sorts of criminal. ‘Jack the Ripper,’ for example, who preyed upon working-class women in the autumn of 1888, is also part of English myth, but killers such as he will never be regarded as heroic. In the case of the Whitechapel murders, there was, and is, also an unsubstantiated belief that the killer was a medical man, and therefore a member of the privileged middle classes. Dick Turpin’s popularity among the rural and urban poor during his own lifetime is well-documented. Turpin was hanged at York on April 10 1739, and contemporary reports of the behaviour of the crowd at the execution suggest, even allowing for broadsheet invention and exaggeration, that he already had the status of a working-class folk hero, one of their own according to Hobsbawm’s analysis, much in the manner of the recently-deceased Reggie Kray or his equally popular contemporary ‘Mad’ Frankie Fraser. Even if every account is a fiction, the consistency of reports of flamboyance and bravery at the gallows indicates what the general public were willing, and in fact wanted, to believe; the body of popular songs alone is a testimony to this act of faith. Contemporary Newgate Calendar accounts describe Turpin’s corpse being borne through the streets like a martyred saint before being buried in lime to render it useless for surgical dissection (Wilkinson 195). Richard Turpin was actually the son of an Essex farmer, and was apprenticed to a Whitechapel butcher; hardly a peasant. Nonetheless, he did not prey upon the poor (why should he?), but upon those whom the poor were likely to view as at best socially remote and at worst oppressors. The robbery of a rich merchant or a local landowner therefore symbolically became an act of rebellion. In his Newgate biographies of Jack Sheppard and Jonathan Wild (both eighteenth century outlaws also romanticised by Ainsworth) Daniel Defoe, as Paul J. De Gategno has argued, also saw such outlaws as economic rebels: symbols of disruptive, self-motivated free enterprise against the emerging mercantile system (De Gategno 157-70).

Hobsbawm argues that it was the surplus male population of impoverished communities, the unmarried and the unemployed, who were most likely to become outlaws. This is fundamentally the assertion of Lytton’s novel Paul Clifford, a politically radical, Godwinian novel intended as a critique of social and legal injustice in England. This novel is also centred on the figure of a highwayman, and is four years senior to Rookwood. As Hollingsworth points out, the body of Newgate fiction produced between 1830 and 1847 is being written and published during the long and turbulent modernisation of English Law, where it evolves from a fundamentally medieval muddle of complex common law, with over 200 capital crimes on the statute books, to a recognisably modern system of justice. Hollingsworth wisely draws a line under the picaresque novels of the eighteenth century (although they undoubtedly influence the genre, the pícaro is not generally a heroic figure like the Newgate novel outlaw), and takes Lytton’s Paul Clifford to be the first of what could be reasonably termed ‘Newgate novels.’ Politically, Hollingsworth finds Lytton much more interesting than Ainsworth, under the assumption that there is no real agenda beyond entertaining the reader and making a profit in the latter’s writing. The dates of Hollingsworth’s excellent study parallel the rise and fall of Peel and the Tory party between the disarray following the Catholic Emancipation Bill of 1829 and the repeal of the Corn Laws in 1846. Hollingsworth takes the Newgate period as running from the publication of Paul Clifford in 1830 to Thackeray’s damning satire of Ainsworth and Sue, ‘The Night Attack’, in the February instalment of Vanity Fair in 1847, while taking Lytton’s Lucretia (1846) to be the last truly Newgate novel. I broadly agree, while noting that although the form moves increasingly towards the penny gaffs and the penny dreadfuls from the mid nineteenth century onwards, the relationship between the high literature of writers such as Dickens, Thackeray, the popular entertainment of Lytton, G.P.R. James and Ainsworth, and the work of penny-a-liners like G.W.M. Reynolds, J.M. Rymer and Thomas Peckett Prest is considerably more fluid than Hollingsworth believes it to be. Hollingsworth’s book is basically concerned with the politics of Lytton and Dickens.

The purpose of the then radical Lytton in writing his Newgate novel had been to attack his own society’s criminal justice system; Paul Clifford was the first novel to make such a direct assault on the Law in two decades of repeated and largely unsuccessful parliamentary agitation for reform. In his preface to the 1848 edition, Lytton explained his political purpose in producing Paul Clifford:

A child who is cradled in ignominy; whose schoolmaster is the felon;- whose academy is the House of Correction; who breathes an atmosphere in which virtue is poisoned, to which religion does not pierce – becomes less a responsible and reasoning human being than a wild beast which we suffer to range in the wilderness – till it prowls near our homes, and we kill it in self-defence.

In this respect, the Novel of ‘Paul Clifford’ is a loud cry to society to mend the circumstance – to redeem the victim (Lytton, preface to Paul Clifford).

Unlike Ainsworth’s Turpin, Lytton’s Clifford is not based upon a real historical figure, although he did study the Newgate Calendars for information concerning highwaymen. If there is any similarity between these characterisations, it is in the move away from the stereotypical descriptions of criminal personality in the Calendar towards the more daring flamboyance of legend. Keith Hollingsworth describes Paul Clifford as: ‘the boys’ own outlaw’ (Hollingsworth 68). This fable initially has more in common with Ainsworth’s later novel, Jack Sheppard: Paul is potentially good, but his youthful innocence is corrupted by evil circumstance, much as Jack Sheppard falls from grace under the controlling influence of the malevolent Jonathan Wild; both maintain their honour among thieves as adults, as does Ainsworth’s Turpin. Where the robbers of Lytton and Ainsworth differ is that Clifford, after transportation, is able to start a new life in America as an exemplary member of the community, while Turpin and Sheppard would have no intention of doing any such thing. They accept the Tyburn tree as a necessary, occupational risk. In much the same way that Gay’s characters in The Beggar’s Opera cannot imagine any kind of death other than hanging. ‘Who is there worthy of the name of man,’ says Turpin, ‘that would not prefer such a death before a mean, solitary inglorious life?’ (Ainsworth 53).

The role that Clifford has been created to enact is that of a Godwinian spokesperson against the Law as an instrument of the rich by which they control and subjugate the poor; the metaphor often employed is that of a state of war between the social classes. Godwin had written in 1793 that:

The superiority of the rich, being thus unmercifully exercised, must inevitably expose them to reprisals; and the poor man will be induced to regard the state of society as a state of war, an unjust combination, not for protecting every man in his rights and securing to him the means of existence, but for engrossing all its advantages to a few favoured individuals and reserving for the portion of the rest want, dependence and misery (Godwin 90).

Paul Clifford echoes this with his statement that:

I come into the world friendless and poor – I find a body of laws hostile to the friendless to the poor! To those laws hostile to me, then, I acknowledge hostility in my turn. Between us are the conditions of war (Lytton 200).

We can note here that the erudite Clifford is not speaking the flash dialogue of Ainsworth’s Turpin and Jerry Juniper; he is merely the author’s political automaton rather than a serious attempt at the representation of the life of the criminal in the manner that Dickens would later adopt. Clifford in fact has more than a little in common with Carl von Moor from Schiller’s landmark of German romanticism, The Robbers (1780). Like von Moor (and in a model later adopted by Scott’s chosen successor as master romancier historique G.P.R. James in The Brigand of 1841) (4), Paul Clifford is the terribly brave leader of a gang of outlaws who are content to steal, cheat, fight, whore and drink until the drop inevitably falls beneath their dirty feet while their leader, when not fighting with Shakespearean valour like the poet-warrior that he essentially is, broods existentially upon the moral weight that bears down upon his soul, and decries the social injustice that has reduced such a pious man to the underworld where morals are a luxury for the rich and crime is a necessity for survival. While his nun-raping comrade-in-arms Spiegelberg ‘paces up and down in irritation’ muttering, von Moor admonishes the hopeful young volunteer Kosinsky thus:

Has your tutor been telling you tales of Robin Hood?

– They should clap such careless creatures in irons, and send them to the galleys – exciting your childish imagination, and infecting you with delusions of greatness? Do you itch for fame and honour? would you buy immortality with murder and arson? Be warned, ambitious youth! Murderers earn no laurels! Bandits win no triumphs with their victories – only curses, danger, death and shame – do you not see the gibbet on the hilltop there? (Schiller III.ii).

He finally surrenders himself so that the reward may be used to help a starving man and his family. Clifford likewise laments that the life of the outlaw is without honour, with an ignoble death as inevitable as a life of crime is to a poor man:

Your laws are but of two classes; the one makes criminals, the other punishes them. I have suffered by the one – I am about to perish by the other … Seven years ago I was sent to the house of correction for an offence which I did not commit; I went thither, a boy who had never infringed a single law – I came forth, in a few weeks, a man who was prepared to break all laws! … your legislation made me what I am! and it now destroys me, as it has destroyed thousands, for being what it made me! … Let those whom the law protects consider it a protector: when did it ever protect me? When did it ever protect the poor man? The government of a state, the institutions of law, profess to provide for all those who ‘obey.’ Mark! a man hungers do you feed him? He is naked – do you clothe him? If not, you break your covenant, you drive him back to the first law of nature, and you hang him, not because he is guilty, but because you have left him naked and starving! (Lytton 392 – 393).

Only Clifford’s companion, the libertine Augustus Tomlinson (ironically presented as a philosopher of crime), accepts the reality of the situation over the dreams of Rousseau’s Social Contract:

‘Why, look you, dear Lovett’, [Clifford’s alias] said Augustus, ‘we are all blocks of matter, formed from the atoms of custom; – in other words, we are a mechanism, to which habit is the spring. What could I do in an honest career? I am many years older than you. I have lived as a rogue till I have no other nature than roguery … I am sure I should be the most consummate of rascals were I to affect to be honest … I must e’en jog on with my old comrades, and in my old ways, till I jog into the noosehempen – or, melancholy alternative, the noose matrimonial!’ (Lytton 328).

As to the rest of the gang: MacGrawler is happy to have a roof over his head, albeit a cave in a forest – ‘among the early studies of our exemplary hero, the memoirs of Richard Turpin had formed conspicuous portion’ (Lytton 317) – and food in his belly, while Ned is happy with wine, women and song. Clifford, who is more at home in Plato’s cave than in Turpin’s, is, like von Moor, an exile in the underworld rather than a true outlaw in the sense that Ainsworth prefers to portray them. Ainsworth’s trick is to move the likes of Spiegelberg and Augustus Tomlinson to centre stage in the guise of the noble robber to see how they might interact with normal society if unrestrained by a pious authority figure like von Moor or Clifford.

Throughout Rookwood, Turpin is a wild card: unpredictable, unrepentant, elemental, free from conventional social constraint, able to change his identity at will, and ride with supernatural speed, while also able to confront his own mortality and still drink and sing and enjoy himself (A similar attitude towards life and death can be seen in the elegant gangster movies of the Japanese director Kitano Takeshi.) If the literary antecedent of Lytton’s highwayman is Schiller’s robber, then Turpin’s is as surely Gay’s MacHeath. As Empson wrote in his radical analysis of The Beggar’s Opera, ‘Mock-Pastoral as the Cult of Independence’:

The only way to use the heroic convention was to turn it onto the mock-hero, the rogue … The rogue so conceived is not merely an object of satire; he is like the hero because he is strong enough to be independent of society (in some sense), and can therefore be the critic of it … MacHeath means laird of the open ground where he robs people; he is King of the Waste Land (Empson 163).

This reminds us of Hobsbawm’s description of the cultural codes of social banditry, both historically and symbolically. Dick Turpin, ‘a sort of hero,’ enters Rookwood in disguise, as is often the case with Ainsworth’s more intriguing characters (Ainsworth 338). Set two years before the original outlaw’s death, Rookwood introduces ‘Jack Palmer’ in a chapter entitled ‘An English Adventurer’ with an epigraph from Gay, ‘Sure the captain’s the finest gentleman on the road’ (Gay I.iv), thus ensuring that Palmer’s true identity is the worst kept secret in the novel. A drunken discussion promptly ensues between Turpin and the attorney (and the comic relief) Codicil Coates as to the gentlemanly disposition of the highwayman. This dialogue echoes the conversation of thieves in The Beggar’s Opera, and the same ironic blending of the honourable codes of the lawful and the lawless citizen applies until there is little difference between the two; it also makes satiric use of the myth of the highwayman (already more than prevalent in English folklore):

Jemmy Twitcher: But the present time is ours, and nobody alive hath more. Why are the laws levelled at us? Are we more dishonest than the rest of mankind? What we win, gentlemen, is our own by the law of arms, and the right of conquest.

Crook-Fingered Jack: Where shall we find such another set of practical philosophers, who to a man are above the fear of death?

Wat Dreary: Sound men, and true!

Robin of Bagshot: Of tried courage, and indefatigable industry!

Nimming Ned: Who is there here that would not die for his friend?

Harry Paddington: Who is there here that would betray him for his interest?

Matt of the Mint: Show me a gang of courtiers that can say as much. (Gay II.i).

This philosophy is endorsed by the outlaw of Rookwood when Turpin argues that:

‘It is as necessary for a man to be a gentleman before he can turn highwayman, as it is for a doctor to have his diploma, or an attorney his certificate … What are the distinguishing characteristics of a fine gentleman? perfect knowledge of the world – perfect independence of character – notoriety – command of cash – and inordinate success with the women … As to money, he wins a purse of a hundred guineas as easily as you would the same sum from the faro table. And wherein lies the difference? only in the name of the game … Look at a highwayman mounted on his flying steed, with his pistols in his holsters, and his mask upon his face. What can be a more gallant sight? … England, sir, has reason to be proud of her highwaymen’ (Ainsworth 52).

The English Adventurer then entertains the company with a flash ballad commemorating the most notorious thieves of the last hundred years, set to a somewhat recognisable tune (as were the majority of Gay’s airs in The Beggar’s Opera); a useful device that made the songs ideal for the stage, where the audience could sing along. The song is rendered in underworld slang, and the references to the robbers are heavily footnoted by the author for the purpose of historical verification. The lyric is naturally celebratory:

A CHAPTER OF HIGHWAYMEN

Of every rascal of every kind,

The most notorious to my mind,

Was the Cavalier Captain, gay JEMMY HIND!

Which nobody can deny.

But the pleasantest coxcomb among them all

For lute, coranto, and madrigal,

Was the galliard Frenchman, CLAUDE DU-VAL!

Which nobody can deny.

And Tobygloak never a coach could rob,

Could lighten a pocket, or empty a fob,

With a neater hand than OLD MOB, OLD MOB!

Which nobody can deny.

Nor did housebreaker ever deal harder knocks

On the stubborn lid of a good strong box,

Than that prince of good fellows, TOM COX, TOM COX!

Which nobody can deny.

A blither fellow on broad highway,

Did never with oath did traveller stay,

Than devil-may-care WILL HOLLOWAY!

Which nobody can deny.

And in roguery nought could exceed the tricks

Of GETTINGS and GREY, and the five or six,

Who trod in the steps of bold NEDDY WICKS!

Which nobody can deny.

Nor could any so handily break a lock

As SHEPPARD, who stood in the Newgate dock,

And nicknamed the gaolers around him “his flock”!

Which nobody can deny.

Nor did highwayman ever before possess

For ease, for security, danger, distress,

Such a mare as DICK TURPIN’S Black Bess! Black Bess!

Which nobody can deny (Ainsworth 54 – 55).

The fun of the recitation is increased by the singer including himself in the lyric. This is the first of many jaunty songs about highwaymen, whereby the singer augments his discourse by continuing to praise their rank and exploits in terms of modern chivalry, often seconded by the endorsements of Ainsworth’s prominent authorial voice (The most popular being ‘Jerry Juniper’s Chant’, AKA ‘Nix my dolls’, the chorus, ‘Nix my dolls, pals/Fake away!’ translating as, ‘Never mind my friends, carry on stealing!’) The author even compares Turpin to the hero of Trafalgar at one point: ‘Rash daring was the main feature of Turpin’s character. Like our great Nelson, he knew fear only by name’ (Ainsworth 163). ‘A Chapter of Highwaymen’ exceeds even this suggestion of noble equality, by punning on Jack Sheppard’s surname and Biblical imagery when giving the outlaw a ‘flock.’ This parallels Gay’s leitmotif regarding MacHeath. As Empson explains, when MacHeath sings ‘At a tree I shall suffer with pleasure’ (Gay, Air, XXV II.v.), the ‘half-poetical, half-slang word tree applies both to the gibbet and to the cross, where the supreme sacrificial hero suffered, with ecstasy’ (Empson, 185). In Turpin’s song, his subjects may begin as ‘rascals’ in the first line, but they finish as divine.

In the final analysis, it is the sense of freedom attached to this type of outlaw (whether in their own day or in the realm of fiction), as clearly identified in fact by Hobsbawm and in fiction by Empson, which makes the figure of Dick Turpin so appealing: a manifestation of longing for a lost cultural innocence, for an imagined past of adventure, heroism and social justice sought from within an increasingly urban, industrialised and Utilitarian society, the moonlit heaths forever shrinking, becoming less magical by the year. In the opening account of his native Manchester in the eighteenth century from Mervyn Clitheroe, the narrator concludes that:

The rivers that washed its walls were clear, and abounded in fish. Above all, the atmosphere was pure and wholesome, unpolluted by the smoke of a thousand factory chimneys. In some respects, therefore, the old town was preferable to the mighty modern city (Ainsworth, Mervyn Clitheroe 8).

In common with many of Scott’s most memorable heroes (the Jacobite, Highland warriors rather than the mediocre heroes of Lukácsian theory), such as the rebel chieftain of Waverley, Vich Ian Vohr, Ainsworth presents Turpin as the last of his line:

Turpin was the ultimus Romanorum, the last of a race, which (we were almost about to say we regret) is now altogether extinct. Several successors he had, it is true, but no name worthy to be recorded after his own. With him expired the chivalrous spirit, which animated successively the bosoms of so many knights of the road; with him died away the passionate love of enterprise, that high spirit of devotion to the fair sex, which was first breathed upon the highway by the gay, gallant Claude DuVal, the Bayard of the road – le filou sans peur et sans reproche – but was extinguished at last by the cord that tied the heroic Turpin to the remorseless tree (Ainsworth, Rookwood, 163 – 164).

Again, the fate of the character is inevitable. Scott had likewise concluded Waverley with the lament that:

It was my accidental lot, though not born a Highlander … to reside, during my childhood and youth, among persons of the above description; and now, for the purpose of preserving some idea of the ancient manners of which I have witnessed the almost total extinction, I have embodied in imaginary scenes, and ascribed to fictitious characters, a part of the incidents which I then received from those who were actors in them (Scott 340).

In each case, these ancestors are not our ancestors. They can appear in contemporary culture only as ghosts. Like the walls of Ainsworth’s Manchester, his nostalgia offers a simple, almost adolescent view of the past compared with Scott’s (although Scott’s is equally his own idealised invention), where complex moral and social issues are always presented as either black or white.

This seemed to be what the public wanted. When it was written in Fraser’s that, ‘With Mr. Ainsworth all is natural, free, and joyous: with Mr. Bulwer all is forced, constrained and cold’ (Anon 724), the reviewer seems to be endorsing a need for escapism which the heroic pantomime of Rookwood offers but the earnest political intent of Paul Clifford does not. Characters like Dick Turpin are therefore created in a kind of eternal present, being never allowed to grow up. He was still riding to York on the stage of the Gaiety Theatre in 1890, before galloping away to Hollywood in the twentieth century, where he remains, in various guises, alive and well to this day, from Johnny Depp’s Captain Jack Sparrow and his cheery pirate songs, to Guy Ritchie’s sexy Cockney gangsters, and very probably Brad Pitt’s forthcoming interpretation of Jesse James. Such critical accolades were not however quite unanimous when it came to Rookwood; John Forster (who later led the war against Jack Sheppard) wrote in The Examiner that:

Turpin, whom the writer is pleased with loving familiarity to call Dick, is the hero of the tale. Doubtless we shall soon see Thurtell (5) presented in sublime guise, and the drive to Gad’s Hill described with all pomp and circumstance. There are people who may like this sort of thing, but we are not of that number … The author has, we suspect, been misled by the example and success of ‘Paul Clifford’, but in ‘Paul Clifford’ the thieves and their dialect serve for illustration, while in ‘Rookwood’ the highwayman and his slang are presented as if in themselves they had some claim to admiration (Forster 1834) (6).

Despite such occasional suggestions of vulgarity, there were no anxieties expressed in print as yet that this novel, or any other like it, could possibly foster criminal intent among the lower orders; a position that was to alter violently with the commencement of Ainsworth’s pure Newgate narrative, Jack Sheppard, in Bentley’s Miscellany in 1839. As was so often the case within and without an Ainsworth narrative, there was a storm brewing, but that’s another story.

WORKS CITED

Anon. ‘High Ways and Low Ways; or Ainsworth’s Dictionary, with Notes by Turpin.’ Fraser’s, IX (June 1834), pp. 724-8.

Ainsworth, William Harrison. Rookwood, A Romance (1834). Collected Works. London: George Routledge and Sons, 1880.

Ainsworth, Mervyn Clitheroe (1858). Collected Works. London: George Routledge and Sons, 1880.

Bloom, Clive. Cult Fiction: Popular Reading and Pulp Theory. London: Macmillan, 1996.

Bulwer-Lytton, Edward George Earle. Paul Clifford. (1830). Collected Works. London: George Routledge and Sons, 1863.

Carpenter, Richard. Dick Turpin. London: Fontana, 1979.

Carver, Stephen James. The Life and Works of The Lancashire Novelist. New York: Mellen, 2003.

De Gategno, Paul J. ‘Daniel Defoe’s Newgate Biographies: An Economic Crisis.’ CLIO 13 (1984), pp. 157-70.

Ellis, S.M. William Harrison Ainsworth and His Friends, vol 1. London: John Lane, 1911.

Empson, William. Some Versions of Pastoral. London: Penguin, 1966.

Evans, Hilary and Evans, Mary. Hero on a Stolen Horse: The highwayman, and his brothers-in-arms the bandit and the bushranger. London: Frederick Muller, 1977.

Fenin, George N. and Everson, William K. The Western: From Silents to the Seventies. London: Penguin, 1978.

Forster, John. Review of Rookwood. Examiner, May 18 1834.

Friedrich Schiller, The Robbers, trans. F.J. Lamport (1780 London: Penguin, 1979), III.ii.

Gay, John. The Beggar’s Opera (1728). London: Penguin, 1986.

Godwin, William. Enquiry Concerning Political Justice. (1793). London: Penguin, 1993.

Hobsbawm, E.J. Bandits. London: Weidenfeld and Nicolson, 1969.

Hollingsworth, Keith. The Newgate Novel 1830-47: Bulwer, Ainsworth, Dickens and Thackeray. Detroit: Wayne State UP, 1963.

Linebaugh, Peter. The London Hanged, Crime and Society in the Eighteenth Century. London: Penguin, 1992.

Mackay, Charles. Extraordinary Popular Delusions and The Madness of Crowds. 2nd. Ed. London: National Illustrated Library, 1852.

Schiller, Friedrich. The Robbers. (1780). Trans. F.J. Lamport. London: Penguin, 1979.

Scott, Sir Walter. Waverley. (1814). Edinburgh: Robert Cadell, 1838.

Wilkinson, George Theodore. The Newgate Calendar. London, Panther, 1968.

Worth, George J., William Harrison Ainsworth (New York: Twayne, 1972).

NOTES

- ‘The Ride to York’ is approximately 35,000 words in length.

- ‘Let us be Diana’s foresters, gentlemen of the shade, minions of the moon.’ Shakespeare, Henry IV, Part 1, I.ii. 28. This would make Ainsworth’s highwayman a Falstaff figure.

- Rookwood is not a pure Newgate novel; the text is a transitional one blending at least three potentially sympathetic genre styles from the previous generation of literature: gothic, historical, and picaresque.

- Scott’s encouragement of, and friendship with, James is covered in detail in Lockhart’s Life of Scott and S.M. Ellis’s biography of James, The Solitary Horseman, or The Life and Adventures of G.P.R. James (London: The Cayme Press, 1927).

- John Thurtell, son of a mayor of Norwich, friend of George Borrow and murderer of one William Weare, professional gambler, in 1823. Pierce Egan interviewed Thurtell in prison and subsequently wrote two broadsheet accounts of the case.

- As Forster became The Examiner’s literary critic the year before, this review is assumed to be his work.

Copyright © SJ Carver, March 2006

Presented as part of a series of guest lectures on regional history at the University of Central Lancashire.