‘Of Magic and Terror, and Mysterious Symbols’: Batman and the Discourse of the Literary Gothic

Stephen James Carver Ph.D.

Previously unpublished, paper originally presented at the American Image/Text Conference, University of East Anglia, Norwich, June, 2011

Copyright © SJ Carver 2011, 2013

Like the reflection of Poe’s House of Usher in the ‘black and lurid tarn,’ the Batman has been the Gothic Other of the American comic book superhero since his first appearance in National Allied’s Detective Comics # 27 in May, 1939.

The comic book was a still a new medium, and Detective Comics was originally an anthology title, launched in 1937 by the comic book pioneer Malcolm Wheeler-Nicholson. Early issues combined ‘Hard-boiled’ detective archetypes common to pulp magazines like Black Mask (which published Chandler and Hammett), with the colourful, sequential graphics of syndicated newspaper strips, most notably Dick Tracy. Action Comics, based around a new character by Jerry Siegel and Joe Shuster called Superman, appeared in June, 1938, after a brutal corporate takeover ousted Wheeler-Nicholson, and National Allied was absorbed into Detective Comics (later ‘DC’) Inc (Jones, 125). The Batman was created the following year by the itinerant author Bill Finger (until recently uncredited), and the DC illustrator Bob Kane, and was intended to capitalise on the success of Superman.

The arrival of the ‘superhero’ revolutionised the fledgling comic book industry, just as the pulp magazines that had inspired them were merging with paperback novels and passing away, and this separation of popular literature from illustrated stories drew a cultural line between popular fiction aimed at adults (which was text-based), and children (which was graphic).

In Detective Comics, the paradigm shifted without a clutch, the original Batman closely resembling Walter B. Gibson’s violent pulp vigilante, the Shadow. The first ever Batman story, ‘The Case of the Chemical Syndicate,’ borrowed the plot of the 1936 Shadow novel Partners of Peril by Ted Tinsley, and concluded with the Batman punching the bad guy into a vat of acid, icily commenting that this was: ‘A fitting end for his kind,’ before slipping back into the shadows and effortlessly evading the police (qtd. in Bridwell, 25).

The prototypical Superman never killed anyone. Superman was as optimistically Modernist as the pulps had been darkly Romantic. Siegel and Shuster’s influences were Classical, Futurist and Socialist, Superman combining the strength of Hercules with the visual style of Buck Rogers, and the liberal idealism of Roosevelt’s New Deal (Sabin, 61). Clark Kent was based on the comedian Harold Lloyd, and his immigrant status (Kryptonian) symbolised American social inclusivity. Metropolis referenced Fritz Lang’s Expressionist dystopia only in its Machine Aesthetic, while Superman did not originally fight crime, but social injustice.

While Superman stories were utopian science fictions, Batman was Gothic. Bob Kane originally designed a bright red costume with black trunks, wings and a ‘domino’ mask, combining the Flash Gordon fashion of Superman with Johnston McCulley’s masked pulp hero Zorro. Bill Finger, however, immediately understood that Batman need not be an imitation of Superman, but his shadow. As Kane later recalled: ‘Bill said that the costume was too bright,’ advising, ‘Colour it dark grey to make it look more ominous,’ and ‘make him look more like a bat and put a hood on him … take the eyeballs out and just put slits for eyes to make him look more mysterious.’ The wings were discarded in favour of a long cape, ‘scalloped to look like bat wings’ (Kane, 41), and the final costume was a deliberate inversion of Superman’s bold, primary colours. From his first appearance, the Batman was the Sun Hero’s dark twin, essentially playing Satan to Superman’s Adam.

Kane’s initial concept was inspired by the caped killer from the ‘Old Dark House’ movie The Bat Whispers, directed by Roland West in 1930, and based on the Broadway play The Bat by Avery Hopwood and Mary Roberts Rinehart, ‘the American Agatha Christie.’ West was an innovative filmmaker known for horror and early film noir, having previously directed Lon Chaney in The Monster and Chester Morris in The Perfect Alibi. West’s aesthetic was deeply influenced by German Expressionist cinema, and he used low-key lighting to create depth and contrast between light and shadow. Like Murnau’s Nosferatu, West’s Bat was an apparently living shadow anticipating Carl Dreyer’s Vampyr, Bela Lugosi’s Dracula, and, of course, the Batman. The Bat is, however, revealed to be natural rather than supernatural at the conclusion of the second act, using Gothic semiotics to terrorise his victims – the van Gorder family’s narratological predisposition signalled by their belief in Spiritualism. The character of the Bat functions as a Gothic text, destabilising the Realist through competing sign-systems and frames of explanation, until, like a novel by Anne Radcliffe, all is revealed to be smoke and mirrors in the end. As much as the cape and chiaroscuro, this device is what the Batman takes from the Bat:

‘Criminals are a superstitious and cowardly lot, so my disguise must be able to strike terror into their hearts. I must be a creature of the night, black, terrible…’

As if in answer a huge bat flies in the open window!

‘A bat! That’s it! It’s an omen… I shall become a BAT!’

And thus is born this weird figure of the dark… this avenger of evil THE BATMAN (qtd. in Bridwell, 27).

As the Count says in Batman versus Dracula, ‘My legacy has been quite influential’ (Batman versus Dracula, 2005).

Vampire semiotics was then doubled with the related literary archetype of the Romantic Hero. Kane has written that he was also inspired by Douglas Fairbanks’ 1920 movie The Mark of Zorro, placing the Batman, like McCulley’s original Curse of Capistrano, in the Romantic tradition of Schiller, Byron, and Ainsworth, in which outlaws and anti-heroes fought corruption in disguise (Kane, 41). In Frank Miller’s Batman: The Dark Knight Returns, The Mark of Zorro (updated to the 1940 remake) is the movie that the Bruce Wayne saw with his parents on the night of their murder, while in The Dark Knight Strikes Again Batman carves a ‘Z’ across Lex Luthor’s face.

Bill Finger, meanwhile, an avid reader of Victorian mysteries, suggested the persona of the ‘scientific detective’ to Kane as an alternative to the outlaw/vigilante (Kane, 43). Batman stories frequently cite Conan Doyle and Poe, although the latent influence of the latter’s confessional Gothic is more interesting. ‘The Purloined Letter’ is Bruce Wayne’s favourite story, and by Detective Comics # 31 Batman had already fought a giant, homicidal ape in Paris. While blending narratological elements from Victorian and pulp fiction, the unifying setting was the fragmented experience of the modern city. The dark urban labyrinths of London and Paris were transposed to Gotham (New York) City, and disorientation was topographical, moral, and textual. Narrative and mise-en-scène were therefore hybrid Gothic/Noir, with Superman’s Metropolis and Batman’s Gotham as oppositional as Heaven and Hell. In Gotham, transgression and taboo were, apparently, permitted – gangsters ruled through corrupt police and politicians, while the Batman fed Arkham with insane theatrical villains drawn to him like moths to a flame.

The final element of the character appeared six months after his print debut. Detective Comics #33 was prefaced by a two-page story entitled ‘The Legend of the Batman – Who he is and how he came to be,’ which was pure Revenge Tragedy, a dramatic form at the heart of the eighteenth century Gothic (Walpole’s Castle of Otranto, for example, leans heavily on Hamlet). We all know the story. Bruce Wayne’s parents are shot before his eyes, and the traumatised child vows to ‘avenge their deaths by warring on all criminals’ (qtd. in Bridwell, 27).

Unlike Superman’s original adversaries, early Batman villains were also overtly Gothic. The ‘mad scientist’ and ‘vampire’ archetypes therefore appeared almost immediately. Dr. Death was essentially Frankenstein, while the Mad Monk, an ancient Hungarian Vampire, was even more like Dracula than Batman, who shot him in the face with a silver bullet. Clayface, meanwhile, was an insane Hollywood horror star called Basil Karlo, who murdered his supporting cast in character: ‘He had played so many horror roles,’ explains Batman, ‘that they had taken possession of his mind’ (qtd. in Bridwell, 87). This story, from June 1940, introduced the recurrent theme of performance annexing performer – the most obvious case being Bruce Wayne’s relationship with Batman, both personas often referring to the other, like Dr. Jekyll, in the third person.

The nineteenth century ‘divided self’ Gothic archetype, revealing the internal origin of the Other, is implicit within all dual identity superhero narratives, although not seriously explored until the 1980s, in the work of Frank Miller, Grant Morrison, and Alan Moore. In Watchmen, for example, the alienated, uncompromising, and right-wing Rorschach (his costume a combination of pulp private eye and psychosis test), is an obvious allegory of Batman, while in The Killing Joke, Moore presents Batman and the Joker as ‘mirror images of each other’ (Moore, 2001), a theme developed in Christopher Nolan’s recent movie The Dark Knight. As Frank Miller has explained: ‘The Batman folklore is full of doppelgängers for Batman’ (Pearson and Uricchio, 36). Miller’s Batman is a voice in Bruce Wayne’s head, which ultimately takes possession of the weaker Self: ‘The time has come. You know it in your soul, for I am your soul. You cannot escape me, you are puny, you are small, you are nothing – a hollow trap that cannot hold me’ (Miller, Dark Knight Returns, 17).

Paul Leni’s The Man Who Laughs (1928) – an Expressionist adaptation of the Gothic Romance by Victor Hugo – was the inspiration for Batman’s carnivalesque Moriarty, The Joker, who debuted in the first issue of Batman Comics in May 1940. The Joker shares the features of Conrad Veidt’s tortured protagonist Gwynplaine, who had a smile carved permanently onto his face by Comprachico surgeons in Universal’s bizarre follow-up to The Phantom of the Opera. The first Joker story also returns to the plot of The Bat Whispers, with the Joker, like the Bat, announcing his plans to radio news stations in advance to maximise terror. (The Joker may also be based on the Shadow villain ‘The Grim Joker’ created by Ted Tinsley in 1936, but the common source is certainly Leni’s movie.)

In April 1940, Detective Comics # 38 introduced Robin the Boy Wonder. Batman stepped out of the darkness and assumed a paternal role. He teamed up with Superman, began fighting crime during the day, and handing criminals over to the police. Robin was added because Bill Finger wanted someone to play Watson to Batman’s Sherlock Holmes, while the publishers wanted to make the character safer – more like Superman than the Shadow. Sales doubled virtually overnight, re-aligning Batman with a younger audience and away from his darker adult origins.

DC was also responding to a Chicago Daily News article that was syndicated on Batman’s first anniversary, in which Sterling North denounced the new medium and its publishers as ‘guilty of a cultural slaughter of the innocents.’ North claimed that comic books were a ‘hypodermic injection of sex and murder,’ sensationally concluding that: ‘Unless we want a coming generation even more ferocious than the present one, parents and teachers throughout America must band together to break the “comic” magazine’ (qtd. in Krensky 27). This argument was given scientific credibility by the psychiatrist Fredric Wertham, who began publishing on the relationship between comic books and juvenile delinquency in 1948. Wertham, a German Jew, likened the superhero comic to the ‘Nazi myth of the exceptional man who is beyond good and evil,’ while Batman and Robin were a ‘wish dream of two homosexuals living together,’ and Superman’s female double, Wonder Woman, was ‘the lesbian counterpart’ (Wertham, 97, 190-192). Church groups and PTAs burnt comic books in the street, while publishers appeared before the senate subcommittee on juvenile delinquency. The subcommittee’s interim report concluded that: ‘this nation cannot afford the calculated risk involved in the continuing mass dissemination of crime and horror comics to its children’ (qtd. in Springhall, 139). Censorship would have been a violation of the First Amendment, but the message was clear. The industry chose self-regulation. The Comics Magazine Association of America was founded in 1954, with editorial standards to be monitored by the independent Comics Code Authority. ‘General Standards’ included:

Respected institutions shall never be presented in such a way as to create disrespect for established authority.

Stories shall emphasise the value of the home and the sanctity of marriage.

Scenes of excessive violence shall be prohibited.

Inclusion of stories dealing with evil shall be used … only where the intent is to illustrate a moral issue … In every instance good shall triumph over evil (Benton, 140).

The medium was rejected as juvenile (rather than adult and literary), aesthetically illegitimate, and morally questionable, while the post-Enlightenment critical discourse of the nineteenth century that had dismissed Newgate and Gothic Romances was re-applied without significant modification.

Batman as a Gothic text returned on the fiftieth anniversary of the character in the graphic novel Arkham Asylum: A Serious House on Serious Earth by Grant Morrison and Dave McKean. Arkham Asylum, like Tim Burton’s Batman movie of the same year, returns to the character’s Expressionist origins and divided self, and is comic book as art book. Morrison later wrote that: ‘The intention was to create something that was more like a piece of music or an experimental film than a typical adventure comic book’ (Morrison, Introduction to Anniversary Edition, 1). The narrative is elaborately intertextual, referencing, for example, passion plays, Lewis Carroll, and Hitchcock’s Psycho. McKean’s graphics are an experimental, mixed-media collage incorporating shadowy, hand-drawn coloured and pencil illustration, oils, and photographs, while central character dialogue appears in distinct, scratchy fonts hand-drawn by letterer Gaspar Saladino. Pages are also balanced, McKean’s symmetrical gridding symbolic of textual and thematic duality. The plot is notionally simple (and has since become a video game, stripped of all original symbolism): the lunatics (led by the Joker) have taken over the asylum, and Batman must restore order in an allegorically charged game of hide and seek, while a parallel narrative tells the story of ‘Mad’ Amadeus Arkham, the asylum’s founder. Arkham meets Aleister Crowley and Carl Jung, which is really the key to the text, which is based around Crowley’s Thoth Tarot and Jung’s theory of archetypes – the relationship between the Self (‘the totality of the psyche’), the Persona (‘a kind of mask’), and the Shadow (the instinctive and irrational) (Jung, 1951). Batman and the Joker physically represent these archetypes. Batman begins as Persona (his mask, says the Joker, ‘is his real face’), defeats a series of shadows, and becomes, for once, a coherent Self (although the Joker reassures him that there will always be a place for him at Arkham) (Morrison, Arkham Asylum, 30, 100). This is mirrored by Arkham’s story, in which the Edwardian psychologist – who bears more than a passing resemblance to Vincent Price – passes through the looking glass and descends into murder and madness, tormented by visions of a giant bat and unholy laughter: ‘born again, into that other world … of magic and terror, and mysterious symbols’ (Morrison, Arkham Asylum, 4).

1989, finally, saw Pat Mills’ Gothic parody of Batman aged fifty in Kingdom of the Blind, in which a middle-aged billionaire vigilante, ‘The Private Eye’ (who murdered his parents as a child), uses the ‘ruler of the night’ rhetoric of the superhero to protect his own wealth and to prey, vampire-like, upon the urban underclass that he despises. ‘The only reason a billionaire becomes a vigilante,’ realises the ‘hero hunter’ Marshal Law, ‘is to hold onto his money’ (Mills, 40).

Since the fiftieth anniversary, the Gothic Batman remains visually, but not textually, as his multi-media narratives repeatedly follow the original dark-to-light cycle of 1939 to 1940. This can be simply demonstrated by the Batman movie franchise, which went from the kinky Caligarism of Burton’s Batman Returns in 1992 to Joel Schumacher’s Batman Forever in 1995, which re-introduced Robin.

Christopher Nolan’s 2005 Batman Begins returned Batman to the darkness, by resurrecting the Gothic Immortal Ra’s al Ghul (‘the demon’s head’), the 500-year-old founder of the secret brotherhood ‘The League of Shadows.’ Batman is given a Theosophical origin, as Bruce Wayne, like Madame Blavatsky, studies under the Himalayan Master. (In the 30s, the Shadow had also ‘travelled through East Asia.’) The blend of orientalism and occultism in this character – originally created by Denny O’Neil and Neal Adams in 1971 – clearly signals the influence of Bulwer-Lytton’s 1842 Gothic Romance Zanoni: A Rosicrucian Tale, the main Western source of Hidden Master mythology. (In the same film, the Scarecrow also returns to the Jungian archetypes of Arkham Asylum.) In Nolan’s sequel of 2008, The Dark Knight, Heath Ledger’s Academy Award winning Joker is a synthesis of the 1940 pulp original and the Lord of Misrule from Morrison’s Arkham Asylum, and is firmly established as a twenty-first century ‘Goth’ icon. The announcement that the forthcoming third instalment, The Dark Knight Rises, will feature Anne Hathaway as Catwoman does not, however, bode well. As IGN notes: ‘We’re ultimately expecting a more uplifting ending for Batman than before’ (Schedeen, 2011).

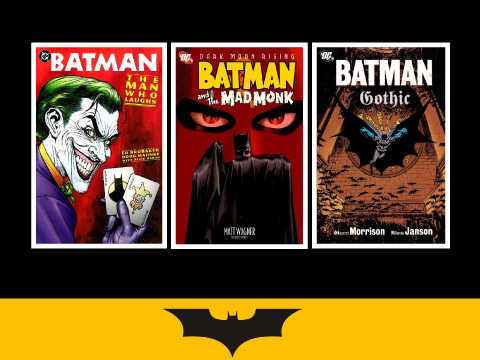

Now over seventy years old and a global brand, the Batman, like Dorian Gray, remains forever young, his simple story endlessly retold, re-invented, and re-imagined across media. Within this shifting field of signs, Batman’s Gothic origins continue to show, in much the same way that Robin’s peek-a-boo mask conceals his true identity with all the conviction of a negligee. Ed Brubaker’s recent update of the origin of the Joker, for example, is titled The Man Who Laughs, while Steve Niles’ Gotham After Midnight is a pastiche of Tod Browning’s London After Midnight, and Grant Morrison’s fusion of Matthew Lewis’ The Monk and Poe’s ‘Masque of the Red Death’ is called, simply, Gothic. The Mad Monk has also returned. Beyond this self-referential intertext, the visual style of the character has become increasingly Expressionistic, particularly in the art of Doug Moench, but in a hyper-real frame, or, in the words of Frank Miller, ‘a lot of third rate imitations’ (qtd. in Pearson and Uricchio, 35). The Batman’s principle motive remains revenge, and Bruce still has bats in his belfry – the conflict is never reconciled. As the Gothic denies wholeness and progress, Batman’s monomyth, his hero’s journey, becomes a road to nowhere, ending in the same darkness in which it began, as his parents die a thousand deaths. The doppelgänger leitmotif remains implicit, constantly threatening self-disintegration, just as aberrant and ambivalent Gothic signifiers threaten to destabilise the commercial intertext, turning graphic novel, like Gothic novel, into anti-novel.

Like Freud’s theory of the fantastic narrative, the original Gothic Batman represents the return of the repressed within the global corporate discourse, a narratological free radical in which the text is doubled again, between the morally juvenile and easily marketable character maintained by DC and its parent company Warner Communications, and the tortured soul on the brink of insanity, saved from the abyss only by his mission, desired by the majority of fans and glimpsed in the shadows, from time to time, in graphic narratives like Arkham Asylum and The Dark Knight Returns. ‘Striking terror,’ says Miller’s Batman, is ‘the best part of the job’ (Miller, Dark Knight Strikes Again, 110). Comic books remain at the periphery of literary culture. Like the Gothic narrative, they interrogate the ‘Real,’ and invite us to transgress. There is always room in the asylum…

Works Cited

Batman versus Dracula. Dir. Brandon Vietti. Warner Home Video, 2005.

Finger, Bill, and Kane, Bob. ‘Clayface.’ Detective Comics 40 (June 1940). In E. Nelson Bridwell, editor. Batman From the 30s to the 70s. London: Hamlyn, 1972.

—. ‘The Case of the Chemical Syndicate.’ Detective Comics 27 (May 1939). In E. Nelson Bridwell, editor. Batman From the 30s to the 70s. London: Hamlyn, 1972.

—. ‘The Legend of the Batman – Who he is and how he came to be.’ Detective Comics 33 (November 1939). In E. Nelson Bridwell, editor. Batman From the 30s to the 70s. London: Hamlyn, 1972.

Jones, Gerard. Men of Tomorrow: Geeks, Gangsters and the Birth of the Comic Book. New York: Basic Books, 2004.

Jung, C. G. Aion: Researches into the Phenomenology of the Self (Collected Works Vol. 9 Part 2). Princeton: Bollingen, 1951.

Kane, Bob, with Andrae, Tom. Batman and Me. New York: Eclipse, 1989.

Krensky, Stephen. Comic Book Century: The History of American Comic Books. Minneapolis: Twenty-First Century Books, 2008.

Miller, Frank, and Varley, Lynn. Batman: The Dark Knight Strikes Again. London: Titan, 2003.

Miller, Frank, Janson, Klaus, and Varley, Lynn. Batman: The Dark Knight Returns. London: Titan, 1986.

Mills, Pat, and O’Neill, Kevin. ‘Kingdom of the Blind’ (1989). In Pat Mills and Kevin O’Neill. Marshal Law: Blood, Sweat and Fears. London: Titan, 2003.

Moore, Alan. Interviewed by Brad Stone. Comic Book Resources (October 22, 2001). Available from: http://www.comicbookresources.com/?page=article&id=511 (Accessed June 5, 2011).

Morrison, Grant, and McKean, Dave. Arkham Asylum: A Serious House on Serious Earth. London: Titan, 1989.

Morrison, Grant. ‘Introduction.’ In Grant Morrison and Dave McKean. Batman: Arkham Asylum – Anniversary Edition. London: Titan, 2005.

Murphy Charles F. ‘Code of the Comics Magazine Association of America, Inc.’ (Adopted October 26, 1954). In Mike Benton. The Illustrated History of Horror Comics. Dallas: Taylor Publishing, 1991.

Pearson, Roberta E., and Uricchio, William, editors. The Many Lives of the Batman: Critical Approaches to a Superhero and his Media. New York: Routledge, 1991.

Sabin, Roger. Comics, Comix & Graphic Novels: A History of Comic Art. London: Phaidon, 1996.

Schedeen, Jesse. ‘Everything We Know About The Dark Knight Rises.’ IGN (May 20, 2011). Available from: http://uk.movies.ign.com/articles/114/1145692p1.html (Accessed June 6, 2011).

Springhall, John. Youth, Popular Culture and Moral Panics. London: MacMillan, 1998.

Wertham, Fredric. Seduction of the Innocent. London: Museum Press, 1955.

Great post, I have yet to write my own post on this topic, but I love the links of Batman to Gothic elements.

[…] Man Who Laughs – an adaptation of Victor Hugo’s novel of the same title. The main protagonist Gwynplaine had an unnaturally toothy smile carved onto his face which a feature and its explanation were […]